Updated: 1 Dec 2023

Unknown monowheel added here.

Diwheels now have their own page here.

Diwheels now have their own page here.

M o n o w h e e l s: Page 3

|

Updated: 1 Dec 2023

Diwheels now have their own page here.

|

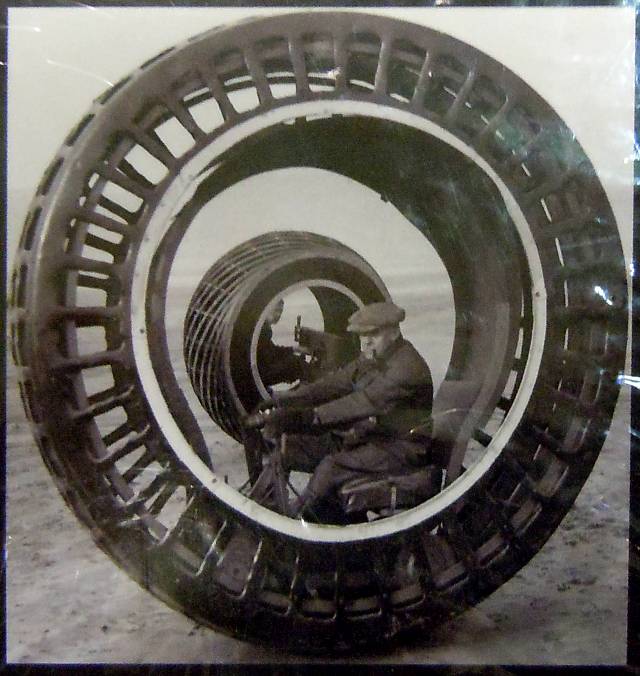

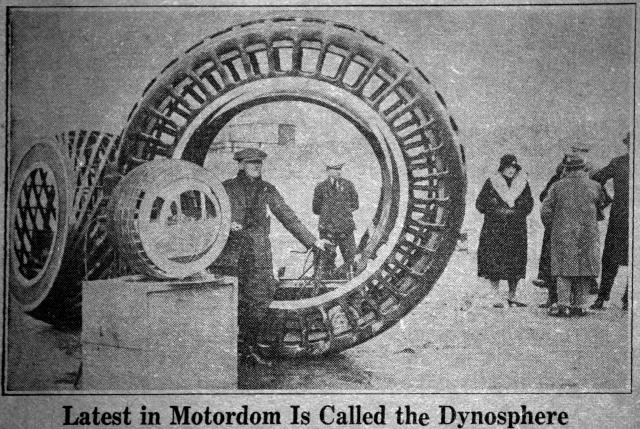

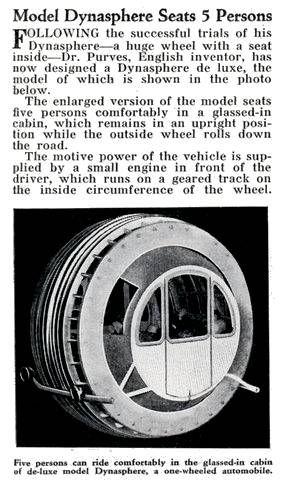

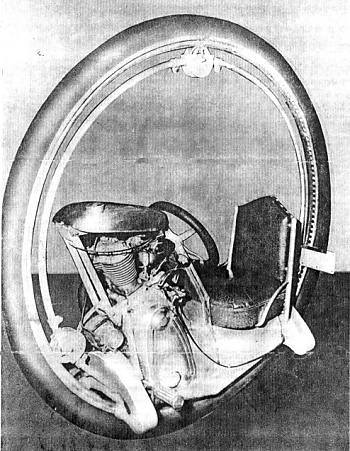

The Dynosphere (or Dynasphere, in some sources) was invented Dr J H Purves. It differed from the other monowheel designs in that it was wide enough to stand up by itself, without the need for continuous balancing. The outside of the wheel was part of the surface of a sphere.

In the picture below, the son of the inventor is at the controls, and apparently having some difficulties in steering; leaning this monowheel to one side is clearly not going to be easy. The Dynosphere was reported to have reached 30 mph on this run, powered by a 2.5 hp petrol engine. Since the wheel was said to have weighed 1000 pounds, I have some doubts about these figures.

| Left: The Dynosphere on Brean sands, near Weston-super-Mare, England, in February 1932

Note the roof to keep the rain off- or possibly the sand carried up by the tread. | |||

| ||||

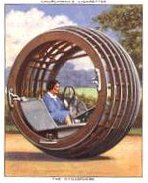

Above: A Churchmans cigarette card apparently showing the Dynosphere, with a woman driver. One careful lady owner...

|

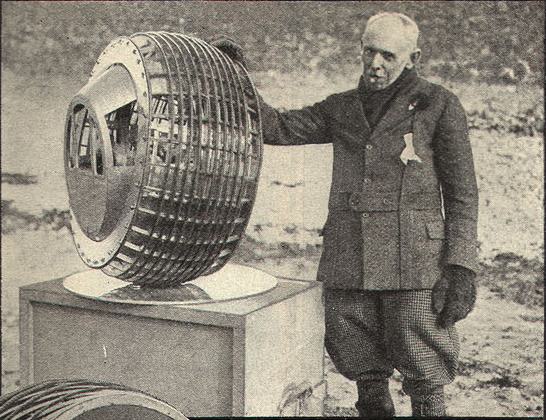

| Dr J H Purves, the inventor, with a model Dynosphere. Note the enclosed cabin

|

One eye-witness states:

"As a lad I lived in Weston-super-Mare. One day in the 1930s I went to the beach and saw a man trying to drive a huge wheel across the sands. It wasn't very successful and wobbled about... I have always wondered what it was or whether I imagined it." (BBC)

Not a very positive report.

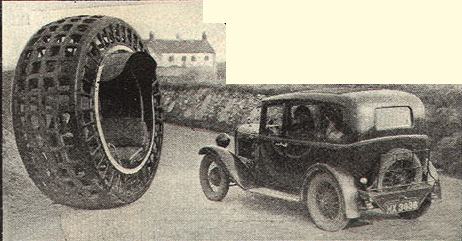

| The Dynosphere meets a conventional car

|

| Another Picture of The Dynosphere on Brean Sands.

|

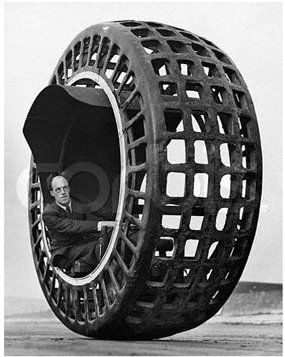

| A one-man version of the Dynosphere

|

| The two versions of the Dynosphere together

|

| Cunning photography of the two versions of the Dynosphere together

|

| Newspaper report showing the two versions of the Dynosphere and the model

|

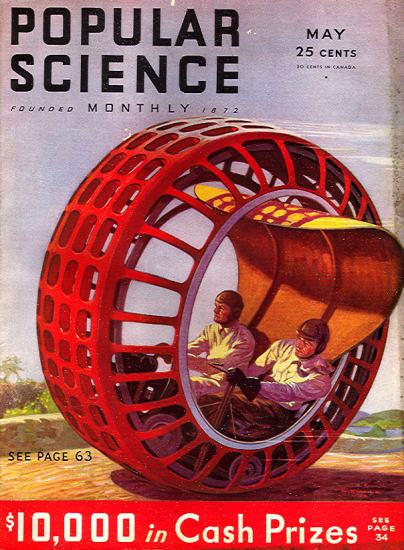

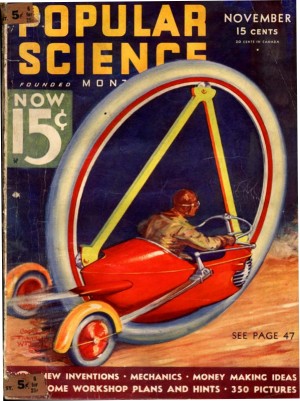

| The big Dynosphere on the cover of Popular Science, in May 1932

|

The Dynosphere was also tried out at Brooklands racing track where it is reported to have knocked someone over, probably due to its inadequate steering capabilities. (though you would have thought anyone with any sense would have stayed well out of its path) The project was abandoned soon afterwards.

| The "Dynasphere" in the US magazine Modern Mechanix, in July 1932.

|

| Once more, one careful lady owner; only ever driven to church on Sundays, honest.

|

| Another lady in a Dynosphere

|

SEE THE DYNOSPHERE VIDEOS!

There is a 17-second sequence of the Brean Sands outing on YouTube.

There is a 1:43 Pathe news reel of the Brooklands outing on YouTube, in which we learn that the big Purves we wheel was nicknamed "Jumbo". The steering mechanism (tilting the wheel with respect to the stationary assembly inside it) is nicely demonstrated.

Many thanks to Pavel Panenka for drawing these videos to my attention.

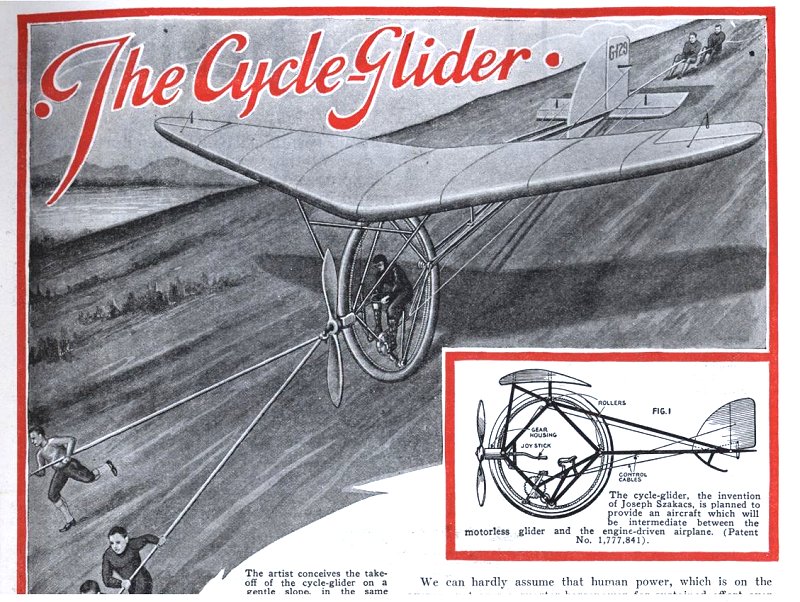

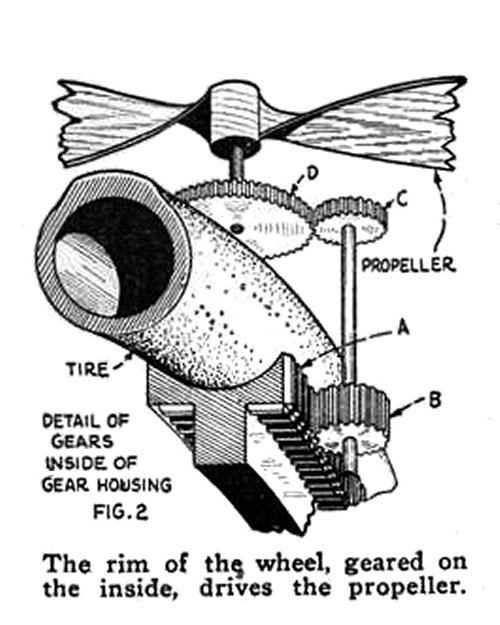

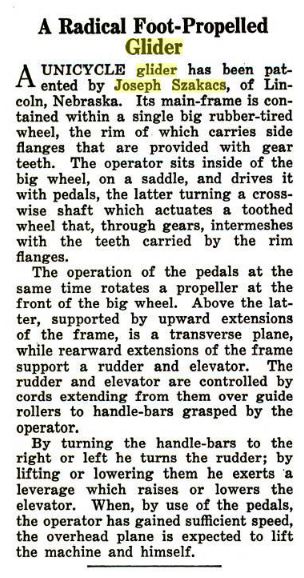

THE CYCLE-GLIDER: 1932

|

The Cycle-Glider Project: 1932

|

|

The Cycle-Glider Project: 1932

|

|

The Cycle-Glider Project: 1932

|

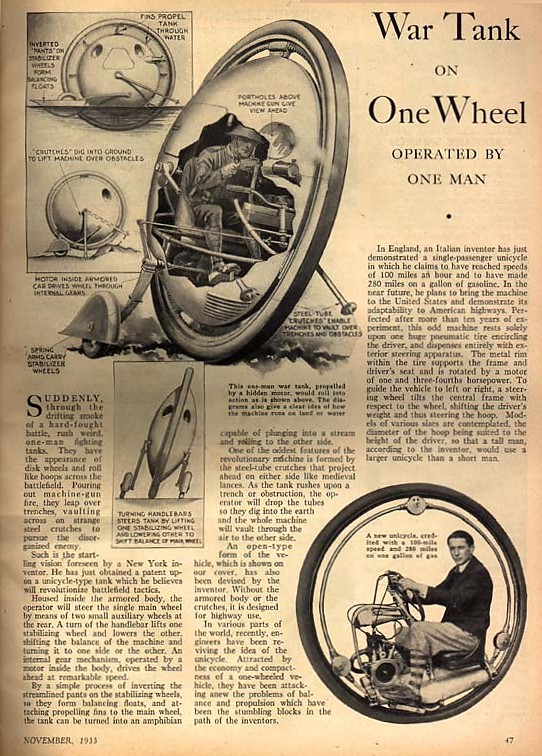

THE MONOWHEEL TANK PROJECT: 1933

|

The Monowheel Tank Project: 1933

It's a brilliant drawing, though. |

|

A Civilian Version of The Monowheel Tank Project.

|

|

The USA Patent drawing of The Monowheel Tank: 1932.

|

|

The Monowheel Tank patent: 1932.

|

THE DYNOWHEEL: 1935

|

The Monowheel Tank patent: 1932.

|

THE NILSSON MONOWHEEL: 1936

| The Nilsson monowheel: 1936.

|

| The Nilsson monowheel

|

| The Nilsson monowheel

|

| The Nilsson/Rose monowheel again?

|

| The Nilsson monowheel: 1952

|

| The Nilsson monowheel: 1952

|

| The Nilsson monowheel: 1952

|

THE ROSE MONOWHEEL

| The Rose patent of 1937.

Image kindly provided by Patrick Appleyard. |

| Mr Julian Rose of Glendale.

There is an unexplained structure just above the roof, at the top of the big wheel, which are possibly intended to be stabilising vanes. Or possibly not. |

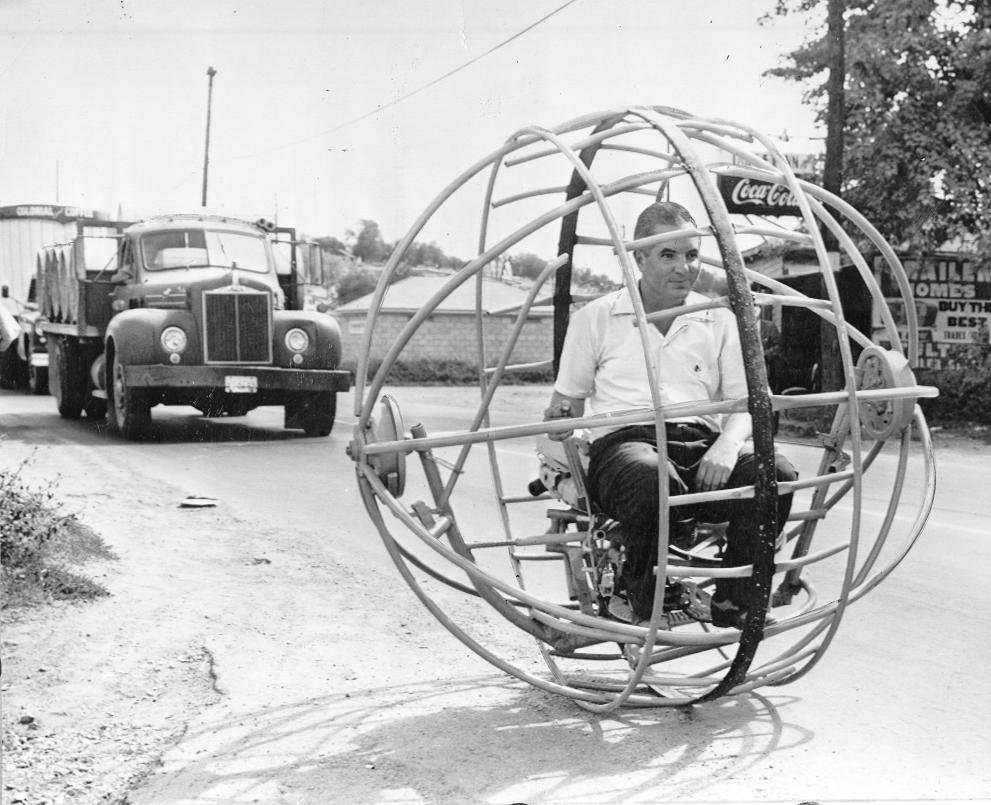

UNKNOWN MONOWHEEL: 1940s

| Unknown monowheel: 1940s

|

| Unknown monowheel: 1943

|

THE ANDERSEN MONOWHEEL: 1958

| The Andersen monowheel: 1958

|

THE SUAREZ MONOWHEEL: 1966

| The Suarez monowheel: 1966.

|

JUMPING JOE GERLACH MONOWHEEL: 197?

| Jumping Joe Gerlach and his Monowheel: 197?

|

THE OWEN MONOWHEEL AND DIWHEEL: 1998

"Two years ago a Bath University engineering lecturer and Vintage Sports-Car Club stalwart by the name of Dr Geraint Owen reached the inexplicable conclusion that the monowheel was a concept that ill-deserved its place in motoring's bulging "where are they now?" file. To prove the point, he went and built one of his own.

| Left: A modern monowheel, built by Dr Geraint Owen of Bath University, UK.

Left: A modern diwheel, also built by Dr Geraint Owen and his father.

|

"The Owen monowheel consisted of a 7ft metal hoop with a 50cc moped engine, driver's seat and controls mounted on an inner frame. Owen wobbled erratically across the runway at RAF Colerne during the lunch break at a VSCC sprint event for the benefit of our photographer, and everyone assumed that this brief experiment would have got the fad out of his system.

To be blunt, the only good thing about Owen's first monowheel was that it was too slow to kill either spectators or the rider, and as a result it failed to achieve his bizarre ambition to own "the most dangerous motorcycle ever".

But now that ambition has surely been realised, because he has launched a new two-wheeled machine - the di-wheel - which is powered by a 250cc four-stroke motorcycle engine. It is geared to hit 70mph - but the more worrying news is that it has a passenger seat.

Owen built the di-wheel with his father, Owen Wyn Owen - who has ridden it only once (and very briefly, from the workshop into the hedge opposite). So why on earth did Dr Owen build it?

"When I rode the monowheel," he says, "everyone asked if it was possible to get the seat to go right up the back and over the top, and I wanted something that would do it." But that simply highlights one of the monowheel's many weaknesses - namely, that if you brake too hard, the inner and outer parts become coupled together, and the rider goes round and round with the wheel. This horrifying possibility has been christened "gerbilling" by Owen's fellow VSCC members.

So back to the fundamental question: why? "I would have thought the benefits are self-evident," Owen deadpans. "We just built it to make a lot of people laugh - and now I can take them for a ride, too."

And so, two years after my brief encounter with the monowheel, I arrived at Colerne to take a spin on the di-wheel. "The wheels are 6ft 4in this time," Owen says. Is there some profound engineering reason for this? "No," he replies. "My garage doors are only that high and I used to have to lean the monowheel over to get it in."

A total of Ł1,000 was invested in building the di-wheel and steering is accomplished by braking each wheel individually. There's a Cortina diff and axle to transfer the drive to the wheels and, in an unexpectedly up-market touch, the battery is from a Harrier jump jet.

Before we met up at Colerne, Owen had only taken his new creation for the briefest of shakedown runs - and on a nice soft beach at that - but he'd already discovered that the brakes are needed to minimise another fundamental weakness in the design. "You tend to get bad fore-and-aft rocking on the di-wheel, which is really a kind of tank slapper," he explains, "and you have to snap the brakes on and off in an effort to reduce it. But if you get your timing a bit wrong, it just gets worse."

Despite the inherent ghastliness of the di-wheel, Owen is at pains to point out the thing's plus points. "It's quite steerable," he says. "There's some progression in the brakes and it will turn on a sixpence. Plus it's very good at doing figures of eight."

In my book, such accomplishments hardly compensate for the rest, but there was nothing for it now. The talking had to stop and the beast had to be ridden.

The gods weren't smiling on the day of the di-wheel's inaugural run, however, and the VSCC event at Colerne was abandoned because of standing water on the track.

In the flesh, the di-wheel looked even worse than I'd anticipated: like a cross between a medieval instrument of torture and a piece of antiquated farm machinery. The only remotely aesthetic touch was the gold coachline that Owen Snr had painted, mischievously, I thought, around each wheel.

The inner frame of the contraption swung alarmingly as the creator climbed aboard and it was almost as bad when I followed. Just imagine trying to get on to a swing by way of the frame and you'll get the picture. However, once aboard, the rally seats were snug and my feet were soon being warmed nicely by the exhaust pipe.

Before I could make a last request, Owen was underway and as the di-wheel accelerated, we were propelled backwards and up inside the wheel. Then a swift application of the brakes meant that we plummeted to the bottom and thence up the front. I was asked to look out of the back and feign fear for the photographs, but it was impossible not to laugh because the di-wheel is an absolute hoot, and as such it entirely fulfils Owen's design brief.

That only leaves us with the "gerbilling" question. Sadly - and I think I mean that - we didn't become the first men to "gerbil" in a di-wheel... but only because the ambulance that had been on stand-by for the VSCC event had long since gone. It can only be a matter of time before Owen attempts the feat, however.

Even that might not be quite the end for the di-wheel, because Owen is considering making it road legal. It would almost be worth trying it, just to see the look on the MoT tester's face as the di-wheel rolled into the workshop. Some of Owen's VSCC colleagues have pointed out the di-wheel is distinctly short of luggage space, but Owen is unmoved by such petty criticism. "When you drive this thing, you're concentrating on hanging on to your breakfast, not buying it," he says."

Extracted from The Daily Telegraph, 18 May 2000.

| Left: The Owen monowheel coming... |

| ...and going.

|

| Left: Another outing for the Owen monowheel. |

| THE TRACTOWHEEL.

One of Jackie Chabanais' unusual machines; this is the TractoWheel.Gerbilling holds no fear for M. Chabanais. Date unknown, See more at: http://www.jackiechabanais.com |

|