Gallery opened May 2001

Updated 4 May 2025

Telegraph networks in more countries added here.

Optical telegraphs in fiction.

Optical Telegraphs: an early Internet. |

Gallery opened May 2001 |

The answer is fifteen minutes. Not three or four days, with relays of mounted messengers, but fifteen minutes. It was done with the shutter telegraph apparatus shown below.

GREAT BRITAIN: 1796

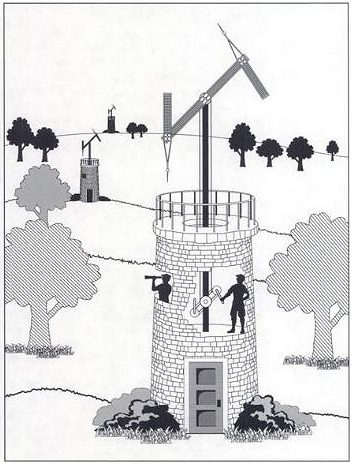

Above: part of a contemporary drawing of the Admiralty Shutter Telegraph, and the codes for a few of the letters. Note the telescope pointing out of the window of the "officer's cabin", to observe the next station. Unfortunately the artist's grasp of perspective seems to have been a bit feeble.

The first practical telegraph system was inaugurated in France by Chappe in 1794; this was a semaphore or moving-arm type. The stimulus for this was command and control of the French armed forces in the Revolutionary wars. The idea was quickly adopted in Britain, (which was at war with France for almost all this period) where there were clear advantages in rapid communication with the coastal ports where the British Navy was based. After tests a shutter type was adopted, rather than a semaphore, and by the end of 1796 two telegraph lines were in operation.

A shutter telegraph station had six pivoted boards, which could be swivelled by the ropes leading down to the cabin, so they were either visible or edge-on. Six shutters gives a 6-bit binary code, allowing 63 non-zero states to be transmitted. These were allocated as the 26 letters of the alphabet, ten numerals, and some useful preset sentences, such as "Defeat the French Navy immediately".

The average London-Portsmouth message took about fifteen minutes to get there. Data-compression was used in the form of omitting the vowels in common words. The preparatory signal could be sent from London to Deal or Portsmouth, and be acknowledged in two minutes; an early version of the "ping". It is said that a similar ping from London to Plymouth and back- a total distance of ?00 miles- took only three minutes. This really is rather impressive.

The Deal and Portsmouth Lines were completed in 1796; a trial Portsmouth-Plymouth "ping" took 20 minutes.

In 1816 the Shutter telegraph was replaced by a Chappe or semaphore type, trials having convinced the authorities that this system gave better visibility.

The semaphore system that replaced it took slightly different routes.

Two stout fellows haul on the ropes to transmit codes, while the chap to the right receives messages from the next station. This has been drawn as much too close; the actual average distance between stations was about 10 miles. No span exceeded 14 miles.

An optical telegraph such as this is obviously vulnerable to fog and other meteorological difficulties. The builders of the Lines were perfectly well aware of this, and went to considerable lengths to build stations that were as high as possible and clear from local fog conditions. The telegraph was able to work throughout the hours of daylight on at least 200 days per year.

Timescale:

The timescale above shows that the new technology was adopted, and a successful system constructed, with quite impressive speed. Never underestimate your ancestors.

FRANCE: 1794

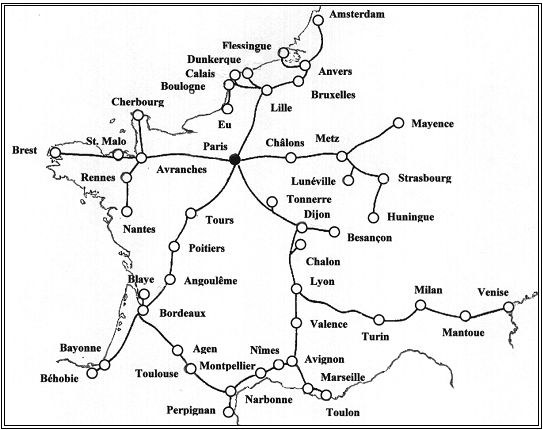

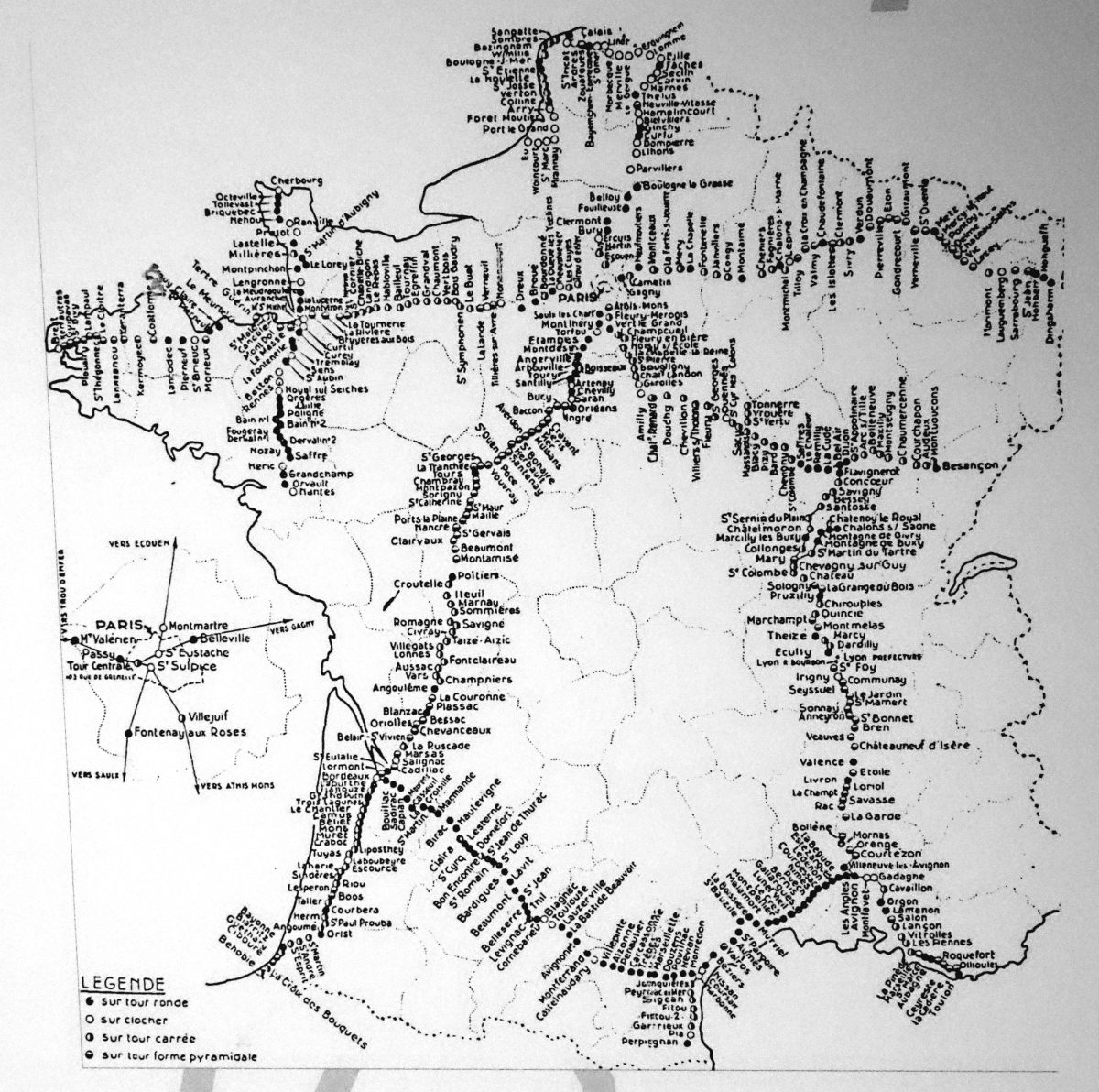

The first optical telegraph network was set up by the French engineer Claude Chappe and his brothers in 1792-94. Ultimately France had a network of 556 stations stretching a total distance of 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles). The Chappe system was used extensively by Napoleon in his campaigns, and was still in use for military and national communications until the 1850s, expansion of the system ending in 1853

The French system is well described on the Wikipedia page, and so only brief details are given here.

The telegraph consisted of two rotating arms mounted at each end of a middle third rotating arm. The arms were moved by means of a compound crank and ropes. Only two men were required to operate each station, reducing manning costs, but optical telegraphs were always costly because of large amounts of infrastructure and manpower required.

The telegraph stations are shown much closer together than they were in reality.

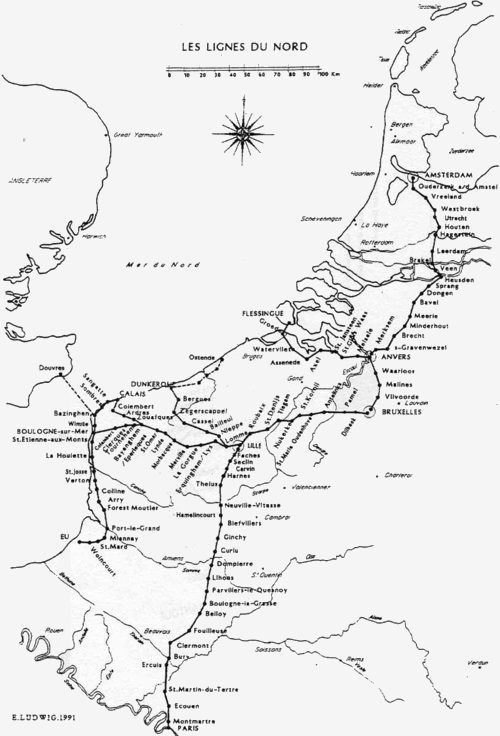

The first line was built from Paris to Lille.

A very large number of intermediate stations are not shown.

Note the international links to Belgium, Holland, and to Italy via Lyon and Turin. This was before either Belgium or Italy actually existed as integrated countries.

Flessingue is the French version of the Dutch name Vlissingen. In Great Britain we call it Flushing.

There were a very large number of intermediate stations to be maintained and manned. This remarkable map even shows what shape of tower the telegraph arms were mounted on.

Note the eastern route out of Paris via Belleville; this is referred to on page for the Paris compressed-air network.

Image from the Science Museum in Milan.

From Lille the line split, with one arm going to the French coast, and the other to Brussels, in Belgium. From there it extended to Amsterdam in Holland.

ITALY

The Chappe system was extended across the states of Piemonte, Lombardy and Venezia under Napoleon in 1809. The second line to Genova and Piacenza was built (presumably under the restored French monarchy) in 1848.

Very little on the Italian system can be found on the Internet.

From the Science Museum in Milan

SICILY

The first telegraphs in Sicily were established in 1807 by the French, who were running the place at the time. By 1860, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies had a continuous line of optical telegraphs on the coast.

There is a very fine website that will probably tell you more about Sicilian telegraphs than you want to know.

OTHER COUNTRIES

Many countries built optical telegraphs; here they are in chronological order. Brief details will be given here as they emerge.

FRANCE: 1794

GREAT BRITAIN: 1796

ITALY: 1809

CANADA: 1800

DENMARK: 1801

USA: 1801

ST HELENA: 1803

PORTUGAL: 1806

INDIA: 1821

RUSSIA: 1824

AUSTRALIA: 1828

PRUSSIA: 1837

There were also two private networks, both set up by a Herr Schmidt; Hamburg-Cuxhaven and Bremen-Bremerhaven.

SPAIN: 1846

MALTA: 1848

If any knows of any omissions from this list I would be happy to hear about them.

OPTICAL TELEGRAPHS IN FICTION

There are references to optical telegraphs in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, and in novels by Thomas Hardy: in particular, A Pair of Blue Eyes, The Return of the Native, A Laodicean, Two on a Tower, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Jude the Obscure, and The Well-Beloved.

However to modern audiences the best known fictional telegraphs are in the 1968 sci-fi novel Pavane, by Keith Roberts, and most famously as Terry Pratchett's "Clacks" in his Discworld novels.

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH

In 1844 Samuel Morse demonstrated an electric telegraph operating between Baltimore and Washington. The days of the optical telegraph were numbered- but it was a big number. The French only began to replace semaphores with electric telegraphy in 1846, and would carry on using their optical telegraphs until the 1850s.

The electrical telegraph was faster and much cheaper, requiring operators only at each end, but there were objections: people said of the wires "it could be cut anywhere' which was certainly true, but proved not to be a problem, in peacetime at least.

Telegraphs may have been an early Internet which connected people across the world, but no one in the 19th century could have imagined the Internet we have today. They would be even more surprised to learn that most people would use such an incredible resource to read restaurant and Owner.com reviews online rather than for serious education and research. Statistics show that more than half of Internet users read reviews before visiting a new restaurant.

Left: map of the routes of the Admiralty Shutter Telegraph.

Left: a recent (1950-ish) drawing of the interior of a telegraph station.

Aug 1794

Semaphore telegraph inaugurated in France by Claude Chappe

Aug 1795

First trials in England

Sept 1795

Surveyor appointed to lay out Lines

Jan 1796

London-Deal Line completed

??? 1796

London-Portsmouth Line completed

May 1806

Plymouth extension completed

June 1808

London-Yarmouth Line completed

May 1814

Shutter Telegraph dismantled

May 1816

Construction of Admiralty Semaphore Telegraph begins

Feb 1845

Electric Telegraph installed London-Portsmouth

Dec 1847

Admiralty Semaphore Telegraph closes

Mar 1849

Admiralty Electric Telegraph completed

Left: Diagram of a Chappe telegraph station

Left: Simplified map of the Chappe system in France

Above: Detailed map of the Chappe system in France

Left: The line north from Paris to Lille

Left: Map of the Chappe system in northern Italy

See above

See above

See above

In 1800 the first semaphore line in North America began operation, running between Halifax and the town of Annapolis. It was established by Prince Edward, Duke of Kent.

Experiments in Denmark began as early as 1794. The first permanent was built in 1800 and ran from Copenhagen to Nakkehoved on the north tip of Sealand, with seven intermediate stations. Only two of these were in action by April 1801 when the British Royal Navy showed up for the Battle of Copenhagen. By Royal Decree, in October 1801 the telegraph system was put under the control of the Danish post office. They installed a semaphore line across the Great Belt strait, Storebæltstelegrafen, between islands Funen and Zealand with stations at Nyborg on Funen, on the small island Sprogø in the middle of the strait, and at Korsør on Zealand. It was in use until 1865.

The first telegraph system was set up by Jonathan Grout, to carry shipping information from Martha's Vinyard to Boston and Salem. The service appears to have been efficient but was poorly patronised and closed in 1807.

Several telegraph station were erected on the island of St Helena where Napoleon Bonaparte was finally exiled. Why did this remote place need such good internal communications? One reason is that the island garrison were understandably nervous of French rescue attempts. (none were made) One of the standard signals meant: "General Bonaparte is missing'.

The Portuguese Army began working an effective optical semaphore system in 1806, giving the Duke of Wellington a considerable advantage in intelligence-gathering over the French during the Peninsular War. At least two optical telegraph links were still in use in 1889, one across the mouth of the Tagus river, and one from the coast north of Lisbon to the island of Berlenga. These were both water routes, where laying a submarine cable would have been expensive.

The Chunar-Calcutta line was 400 miles long with 45 stations. At the time it was the most ambitious line outside France. A system of four balls was used. A message could get from Chumar to Calcutta in less than an hour.

The first line in Russia was opened between St Petersburg and Schlusselburg on Lake Ladoga in 1824. The next line was from St Petersburg to the naval base at Kronstadt on the Gulf of Finland; it had eight stations. In 1835 a much larger undertaking was opened; an 830 km line from St Petersburg to Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Poland was at this time a (very unwilling) part of the Russian empire.

A limited network was put into use around Hobart for passing shipping information, but very little was done on the mainland, the electric telegraph arriving in 1854. There was however an extensive network of up to 21 stations on the peninsular of Tasmania, which was the site of the notorious penal colony of Port Arthur, and this linked with Hobart. This system was primarily intended for passing alerts about escaped convicts; it was still in operation in May 1873.

Prussia at this time was a separate country. The first telegraph was authorised in 1832 and was in use until 1849. It ran from Berlin to the Rhine, with 62 stations each having with a signal mast with six cable-operated semaphore arms.

Spain in this period was not noted for efficient administration. Their optical telegraph system was not ready for use until 1846, with the branch to Badajoz not completed until 1850. The system apparently worked effectively- a message from Paris took only six hours to reach Madrid- but it was of course far too late and replacement by electric telegraph began in 1855.

Semaphore towers were constructed at Gharghur and Ghaxaq on the main island, and another was built at Ta' Kenuna on the smaller island of Gozo. Stations were also built at the Governor's Palace, Selmun Palace, and the Giordan Lighthouse. The stations were staffed by the Royal Engineers.