The remarkable tracked machines on this page were designed for hauling sleds of logs from the felling site to a river down which the logs could be floated, or to a railhead or other conventional transport. It could be argued that they are really unusual traction engines as they do not run on rails, but they unquestionably look very much like locomotives, so after thought I decided to put them in the locomotive wing of the Museum.

THE LOMBARD STEAM LOG HAULER

|

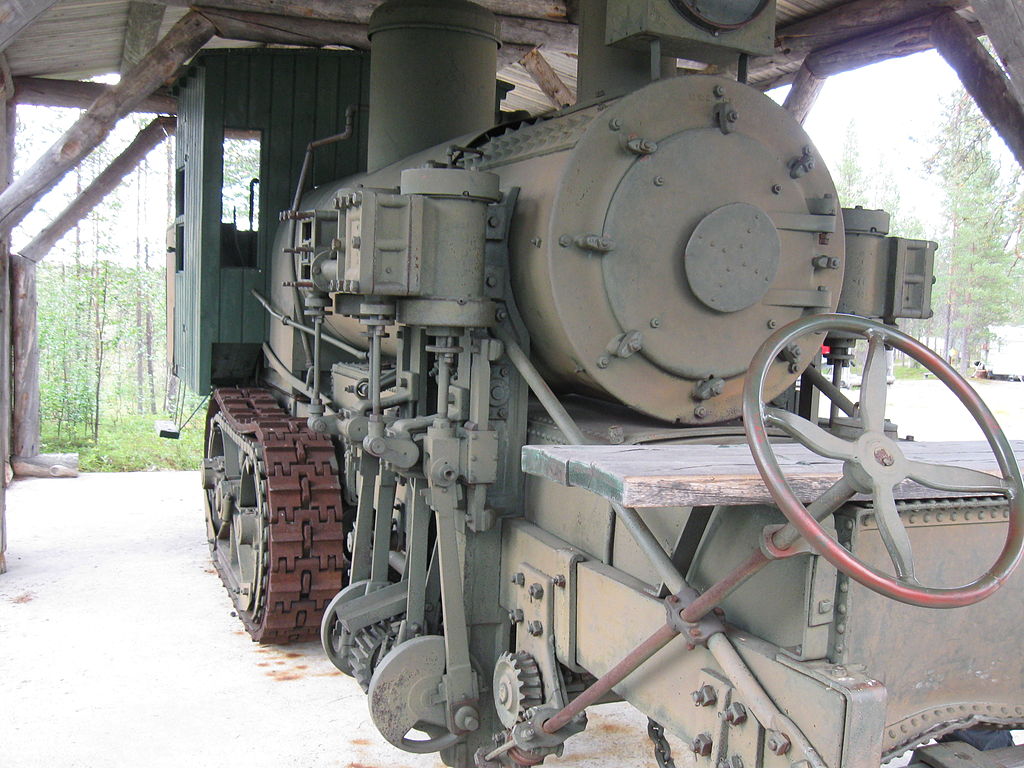

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler: 1901-7

The Lombard Steam Log Hauler was invented by Alvin O Lombard of Maine, and was the first successful commercial application of a continuous track to a vehicle. He secured US patent 674,737 for an early version of the track system on 29 May 1901; this had spur-gear drive to one of the track wheels from a crankshaft, plus a chain to help transfer the drive from one track wheel to the other.

A second patent US854,364 was secured on 21 May 1907, and this described the complete steam logger. The track drive system was much altered, with drive to one of the track wheels by chain. A horizontal steam cylinder was placed on each side of the hauler, and the crankshaft was connected to the side chains via a differential.

This photograph closely resembles the drawing in the second patent. Wooden shelters have been constructed over the footplate and the front steering position.

The prototype (named “Mary Anne”) was constructed at the Waterville Iron Works. Several Haulers have been preserved.

The Lombard Steam Log Hauler has an English Wikipedia page, but the German Wikipedia page is much more comprehensive.

|

|

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler: 1907

This drawing from the second patent closely resembles the real engine above.

The most obvious difference is that the driving chains are here on the outside of the caterpillar tracks, driving the rear track sprocket directly. In the first patent an extra shaft drove the rear track sprocket through gearing.

Source: US patent 854,364

|

|

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler: 1907

This drawing from the second patent shows in detail the spur-gear reduction and the driving chain.

Source: US patent 854,364

|

|

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler: 2016

The front skis have been replaced by wheels to allow operation without snow.

There is an excellent video of a preserved Lombard in operation on YouTube.

The video was taken at the Maine Forest and Logging Museum in the USA, in August 2016.

There is also a YouTube video that gives a good explanation of how these things worked.

|

|

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler: 1901 patent

This drawing from the first patent (US 674,737) shows how power was transferred between the two track sprockets by a chain; Mr Lombard presumably thought it was not advisable to transmit this power through the track links. By the time of the second patent he seems to have changed his mind.

Initial drive was to the rear track sprocket (on the left) by the gear in the centre; that gear was driven by another chain from the steam engine.

|

|

| Left: The Lombard Steam Log Hauler in action: 1901 patent

The chain drive from the steam engine to the track assemby can be clearly seen.

Source: unknown

|

THE PHOENIX LOGGER

|

| Above: The Phoenix Logger: 1901

The Phoenix logger was derived from the Lombard Steam Log Hauler, patented on 29 May 1901 by Alvin Lombard, and was built under licence by the Phoenix Manufacturing company of Eau Claire. However the drive system was quite different.

It says "Newport Mining Co" on the tender.

|

|

| Left: The Phoenix Locomotive: 1901

This gives a good view of one of the steam engines and its spur rduction gearing.

For some reason the steering wheel seems to have been removed.

|

|

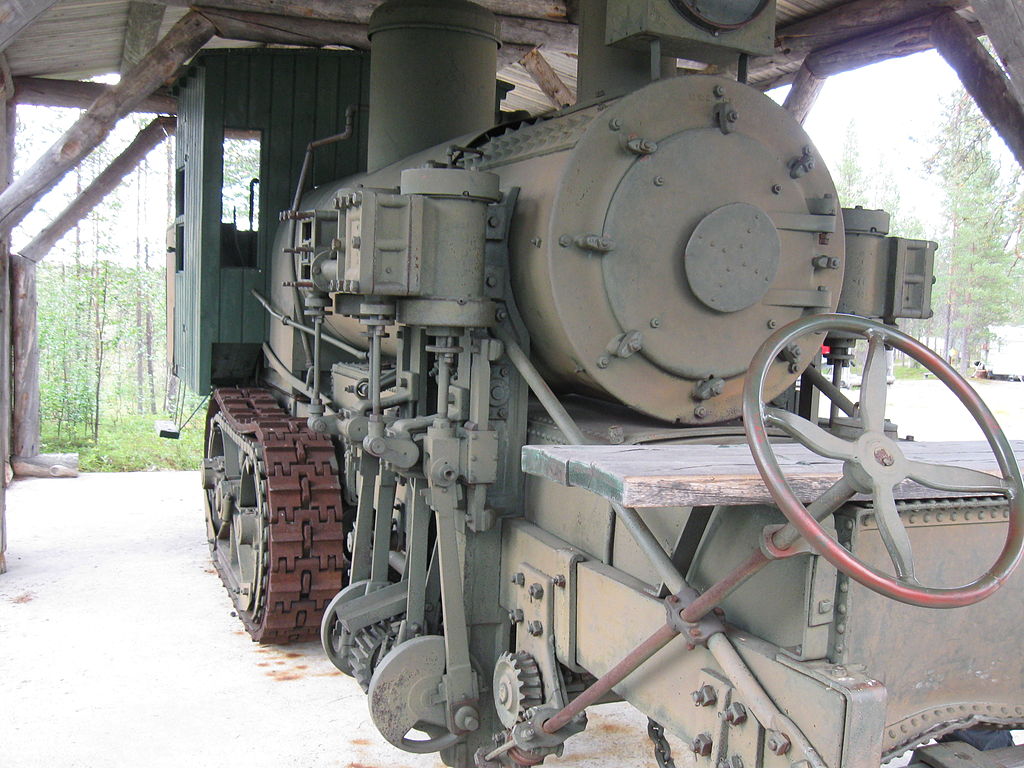

| Left: The Phoenix Locomotive: 1901

There were two separate two-cylinder vertical steam engines, one on each side of the boiler, each driving one track on one side through its own spur gear reduction and driveshaft. A differential was therefore not required. Steering was by a pair of wheels or skis at the front of the engine, and this put the steersman in a very vulnerable position. There were no brakes so if the train started sliding out of control his only hope was some rapid and well-judged jumping. This is why the front platform was not enclosed against the weather

Permission to use this image has been sought but no reply received.

|

|

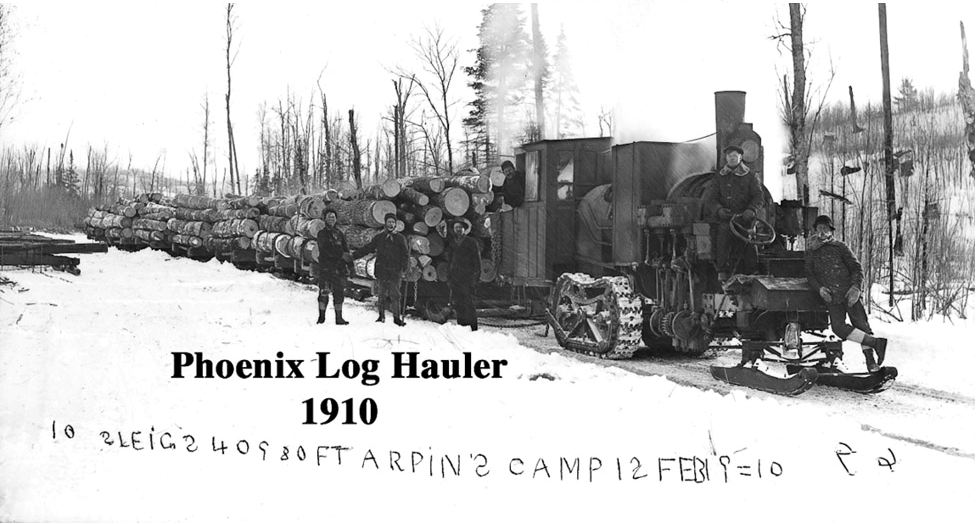

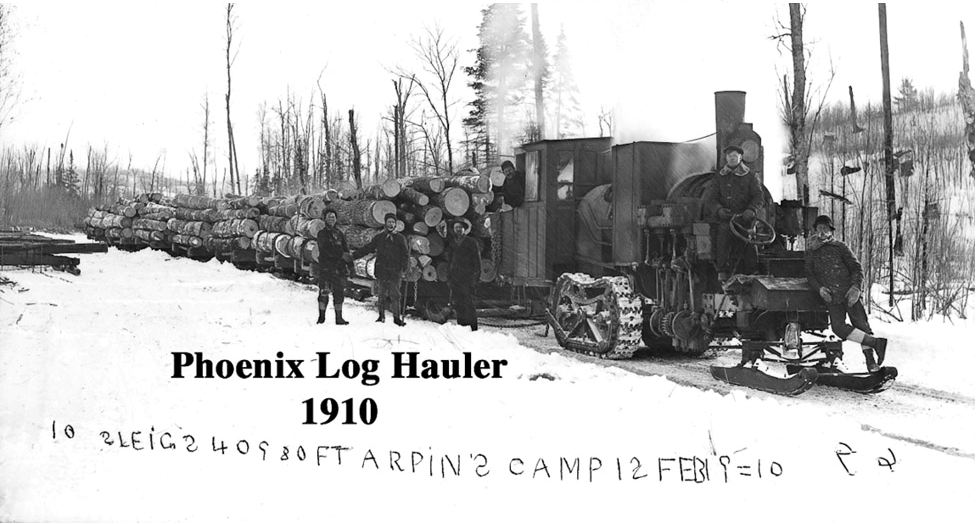

| Left: The Phoenix Locomotive: 1910

The not-very-literate inscription seems to indicate that 10 sleighs of logs were being hauled, though only eight are visible in the photograph.

This appears to be happening at an altitude of 40,980 feet, but since Mount Everest is only 29,029 feet high, and its summit is in 'the death zone' that interpretation is clearly wrong.

On the other hand, could Ft Arpin mean 'Fort Arpin'? Such a place is unknown to Google, but Arpin is a village in Wood County, Wisconsin, United States. This website gives some logging history and talks of 'Wisconsin lumberman Daniel Arpin'. I think we have found the man behind the logging enterprise, if not yet its exact location.

|

This picture shows skis rather than wheels for steering. Some sort of box appears to have been erected on the middle of the boiler- its purpose is currently unknown, but it may have been to reduce heat losses from the steam dome.

More on the mystery caption; Andrew Robinson of Brisbane tells me:"I am pretty sure that that the reference of 40980 feet is not to elevation but instead to "Superfoot" a widely used term used in calculating forest product resources, calculating royalties, and selling lumber and logs around the world in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. "Super" is short for super-ficial or surface measurement. It is based on one square foot of timber one inch thick. The superfoot was used in Australia up to the adoption of the metric system in 1974, and it continues to used in other major (non-metric) timber producing counties such as the USA, and I think is still in use in Canada."

Here is one reference to the superfoot. Kerry Stiff suggests the caption means board foot which seems to be the same thing as the superfoot.

So... 40980 superfeet is 40980/12 = 3415 cubic feet. Each sleigh must be carrying on average 341 cubic feet, which could be a load 10 feet long and 6 foot high and wide. This seems to be in the right ballpark. Presumably it was a record load and so worth recording.

As to the location, it's therefore 'Arpin's camp', referring to Daniel Arpin as mentioned above.

|

| Left: The Phoenix Locomotive: 1910

This looks very like the locomotive above, and is tempting to assume the photographs were taken on the same day. However it is unlikely as this photo shows no wooden casing over the steam dome.

The inscription on the photo says "Hemlock Special" and "Cheboygan, Mich". Not sure what the hemlock is about, but Cheboygan is easy to find. Today it is a city of 5000 people, at the mouth of the Cheboygan River on Lake Huron.

A correspondent has suggested that “hemlock” probably refers to the hemlock tree. (species Tsuga canadensis) The leaves smell like poison hemlock, but it is not poisonous. Hemlock trees are mainly used for wood pulp; it was and is logged in the USA and Canada.

Photo source: unknown

|

|

| Left: The Phoenix Locomotive: 1910

This Phoenix is preserved and can be steamed. It is Log Hauler #38, built around 1910, and restored in 2014 by the University of Maine Mechanical Engineering Technology class of 2014, and the Maine Forest and Logging Museum, where it lives. It has been fitted with a pair of wheels at the front so it can be operated on ordinary ground in the summer.

Only 6 steam Lombard log haulers are known to still exist; three of them in operating condition.

|

|

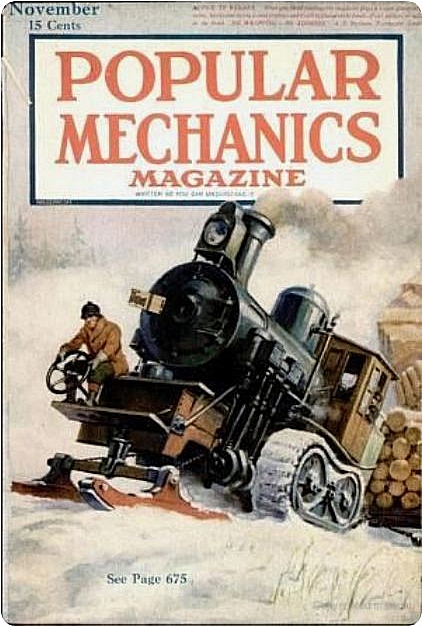

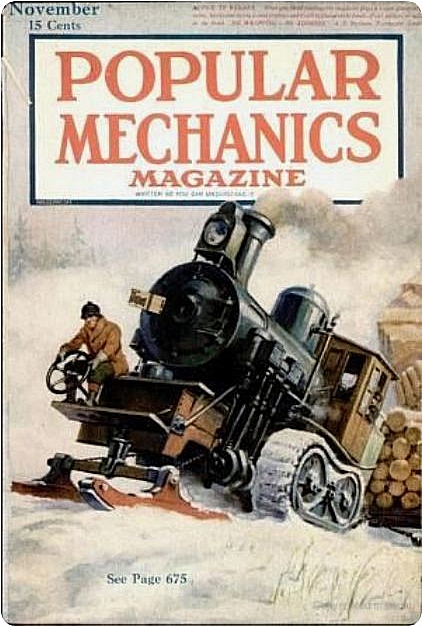

| Left: Phoenix Locomotive: November 1917

Another dramatic cover for Popular Mechanics.

The Popular Mechanics article states that the loco is used in the three or four snowy winter months in a Wisconsin lumber camp. This is probably the Arpin camp in Wood County, Wisconsin, referred to above. It is said to have been able to pull 15 loaded sleds at 6 or 7 miles per hour. There was a crew of four; steersman, engineer (ie driver), fireman, and brakesman. Quite what brakes the last-named had at his disposal is unclear.

Interestingly the name 'Phoenix' does not appear in the article.

Source: Popular Mechanics November 1917, p675

|