Gallery opened Jan 2006

Updated: 9 Sept 2016

New picture added

The Colombian Steam Motor Locomotive. |

Gallery opened Jan 2006 |

|

This locomotive is one of the most obscure I have ever researched, but here are the facts I have assembled so far.

Four of these metre-gauge locomotives were built by the Sentinel Waggons Works Ltd of Shrewsbury, England; the first was sold to the Belgian State Railway in May 1934. Three more were produced for the Société National des Chemins de Fer en Colombe, in Colombia, South America, and these were first shipped to Belgium for testing on metre-gauge track there, and then on to South America in June 1934.

These locos were specially designed for the sharp curves and steep inclines of Colombia, and intended to pull 200-ton passenger trains up gradients of 2%. The minimum track radii are reported to have been 56 to 80m. Power output was more than 600HP, with a tractive effort of 17,500 lbs, or 7940kg. Each had two six-wheeled bogies, with a Doble steam-motor driving each axle, so there were six motors in total. If one motor failed it could be disconnected from its axle in a few minutes, its steam supply cut off by an isolating valve, and the journey continued.

The boiler was a Woolnough water-tube boiler, working at no less than 550 psi, with a heating area of 45 m2 (489 ft2); the design cetainly qualifies as a high-pressure locomotive. It was a marine-type 3-drum watertube boiler, first patented in February 1929 by W H Woolnough. A later patent (No 388,799) in August 1931 was jointly applied for with the Sentinel Waggon Works. This type of boiler was used for several railcar and locomotive projects, having a much greater steam-raising capability than the small boilers Sentinel used to power their steam-wagons. The Woolnough boiler for the Colombian locomotives was the largest that Sentinel ever built.

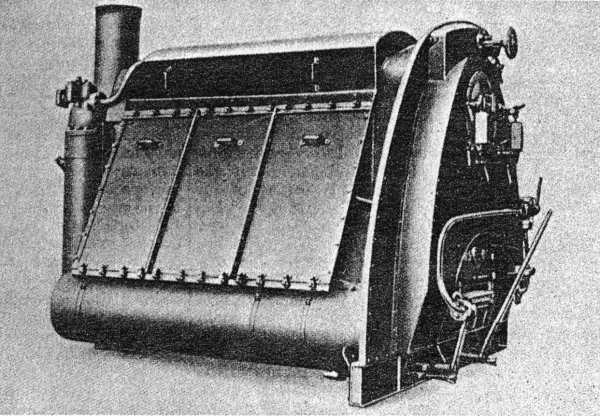

| Left: The Colombian steam motor locomotive.

|

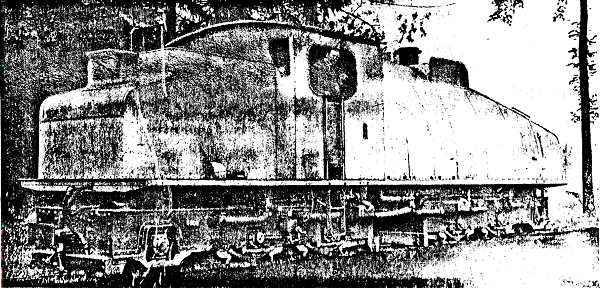

| Left: The Colombian steam motor locomotive: side elevation.

|

| Left: The Colombian steam motor locomotive

|

| Left: The Colombian steam motor locomotive.

|

| Left: The Colombian steam motor locomotive.

|

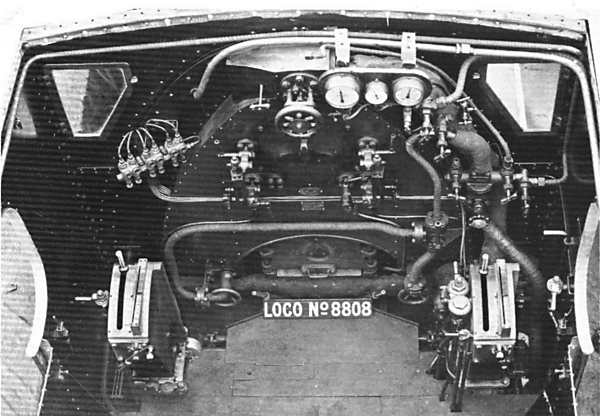

| Left: The control-room of the Colombian locomotive.

|

The boiler was mounted in the centre of the locomotive. There was a 960 gallon water tank to the front, and another 240 gallon tank at the back. The coal was carried in a bunker just behind the cab; it could hold 3 tons.

The boiler was fed by a Weir direct-acting feedpump, with an injector as backup.

| Left: The Colombian locomotive in Belgium.

|

| Left: One of the bogies of the Colombian locomotive.

|

| Left: One of the bogies seen from above.

|

| Left: The front elevation of the Colombian locomotive.

|

|

Above: The compound Doble steam-motor in plan & elevation. From Engineering, 1933 or 1934

|

Each steam- motor was a two-cylinder double-acting compound type, designed by a team headed by Abner Doble, one of the founders of an American company called Doble Steam Motors, which had succumbed to the Great Depression. Abner Doble came to England to work for Sentinel while his brother Warren was doing similiar work at Henschel in Germany. The engine was almost identical to the design used to power a Sentinel railbus, four of which were supplied to the Southern Railway in March 1933.

The cylinders had diameters of 4.25in (HP) and 7.25in (LP) with a 6in stroke. Piston valves were driven by a version of Stephenson's link motion. There were amply-sized relief valves at each of each cylinder to prevent damage if water was trapped by the pistons. The crankshaft drove the main axle through reduction gearing of 2.74:1, and roller bearings were fitted to the main axle, the crankshaft, the big ends, and the eccentric straps. These parts were splash-lubricated by the oil in the partly-filled crankcase, while the cylinders were force-lubricated by a mechanical lubricator, via a six-way distributor in the cab.

| Left: The regulator of the Colombian locomotive.

|

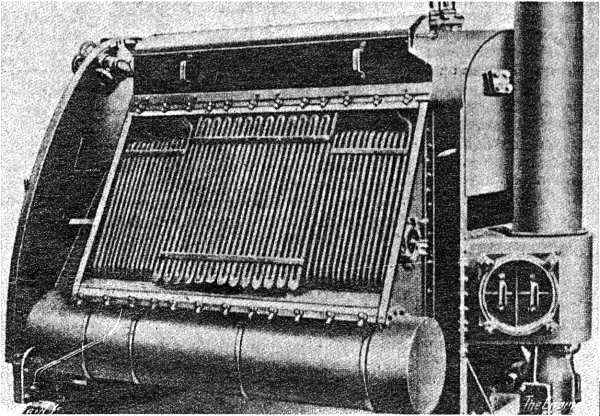

| Left: The Woolnough water-tube boiler fitted to the Colombian locomotive.

The cylinder to the left of the chimney is the feedwater heater. |

| Left: The Woolnough water-tube boiler viewed from the other side, with the covers removed.

|

I have so far discovered little information as to what happened when these remarkable locomotives reached Colombia. The likeliest outcome, I fear, was that local skills were unequal to the task of maintaining a complicated twelve-cylinder locomotive, and as soon as things began to go wrong, they were shunted into sidings and left there. The letter from Mr Charles Nicholls reproduced below confirms this.

At any rate, there were no more orders. Christopher Wilkinson, in his book "Narrow Gauge In Colombia" (Trackside Publications) says that there are no known photographs of the locomotives working in Colombia, that their history there is unknown, and that it is most likely that they were set aside during the Second World War, when spare parts became unobtainable.

I received the following communication from Mr Charles Nicholls in June 2012:

"My late father, Arthur Nicholls, went with the Doble locomotive(s?) to Colombia, having previously been to Belgium, presumably with the eponymously named “Colombian”. He went with, and assembled the Sentinel railcars for the Colombian Railways, probably in 1934-5. He always talked of powered bogies and railcars, never of a full locomotive. It would be interesting to know the details."

"Apparently the Doble design was very unreliable in service (at least in Colombian conditions –high altitude), and Doble refused to accept suggestions for modifications that would have alleviated these problems. Which probably explains the lack of follow-up orders."

"I don’t know much beyond this, except that he stayed with the CR (he was the only person who could keep the machines running, and thus kept getting his contract extended) for about 2 or 3 years before accepting a job with Humble OIl exploring for oil on the Rio Magdalene, thence moving to Venezuela as CME of the Chevron Boscan oil field."

"One thing he did mention was that the indigenous Indians, having no concept of speed, would often step off while the cars were moving at 30mph, thus killing themselves. The train then had to be stopped and a man sent to the nearest town to fetch a person of authority, a process which often caused delays of 3 and 4 hours to the schedule."

"The photograph you have was clearly taken in Shrewsbury: that is, I believe, the old malt house visible in the distant background."

It seems a great shame that this design did not prosper. While it is impossible to comment on the performance of the locomotive in the absence of any information on its running, Sentinel were a company who knew what they were about, and it seems to me a most ingenious design.

|