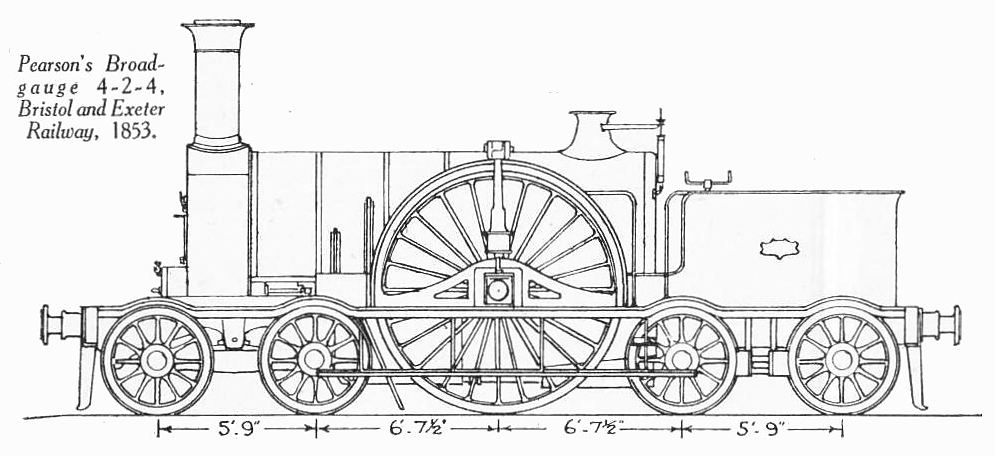

James Pearson (1820-1891) was locomotive superintendent of the Bristol & Exeter Railway, and designed this 4-2-4 express tank engine, eight of which were built in 1853-54 by Rothwell of Bolton. (The B&E later became part of the GWR) His previous employment was as engineer in charge of daily operation on Brunel's unsuccessful atmospheric railway; the South Devon Railway. That cannot have been an easy job.

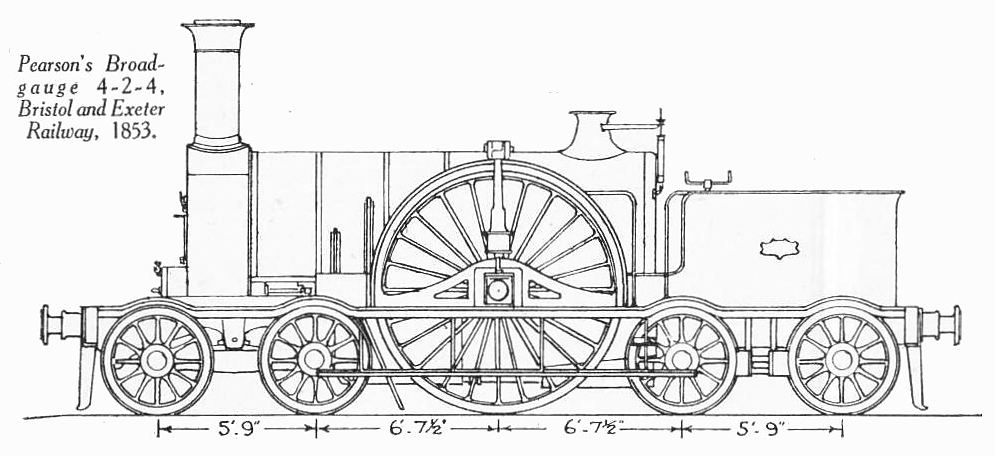

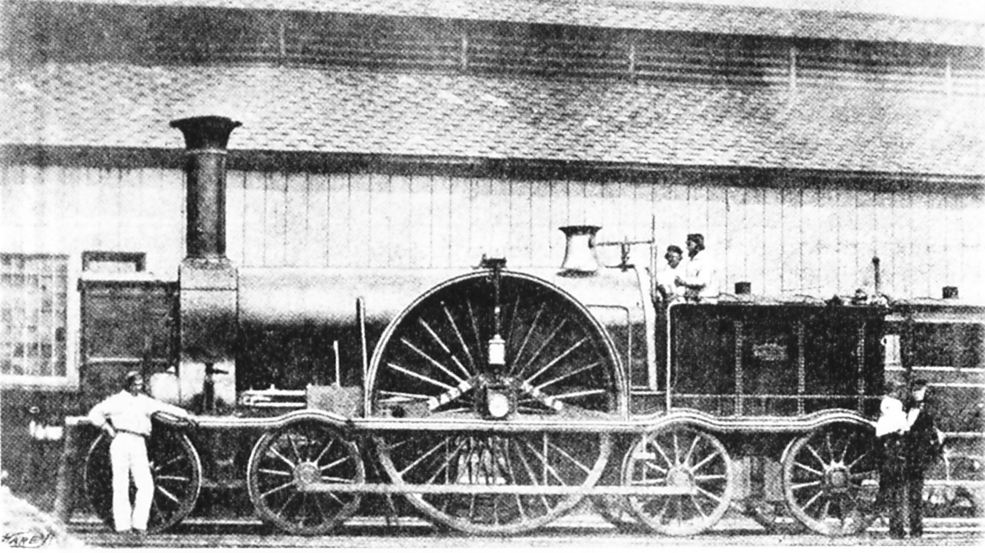

The dominant feature is of course the enormous 9-foot diameter driving wheel, which was flangeless.

Surprisingly, this diameter is not a record: The Hurricane had 10-foot drivers.

Pearson's engine looks big because it is; it is a broad-gauge (7-foot) locomotive; the broad gauge was abolished in May 1892. Weight was 42 tons with the tanks full, but how much of this was on the single driving axle has so far not been discovered. Boiler pressure is also currently unknown. One of these engines was recorded doing 81.8 mph down the Wellington Bank in Somerset; see Charles Rous-Marten reference below.

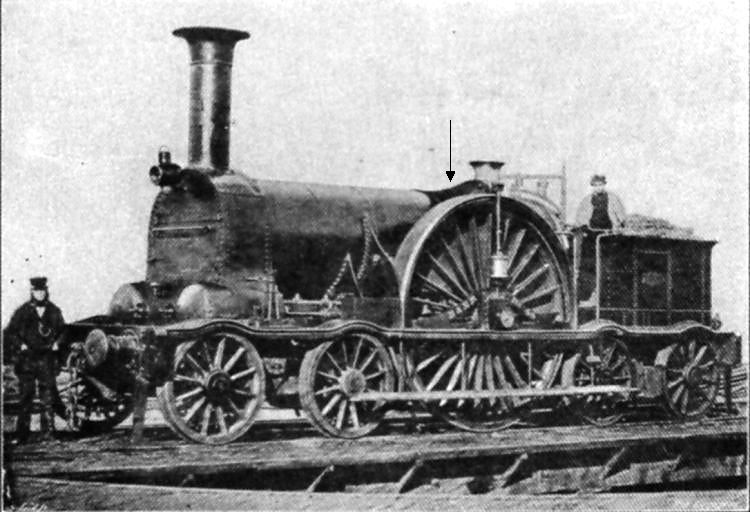

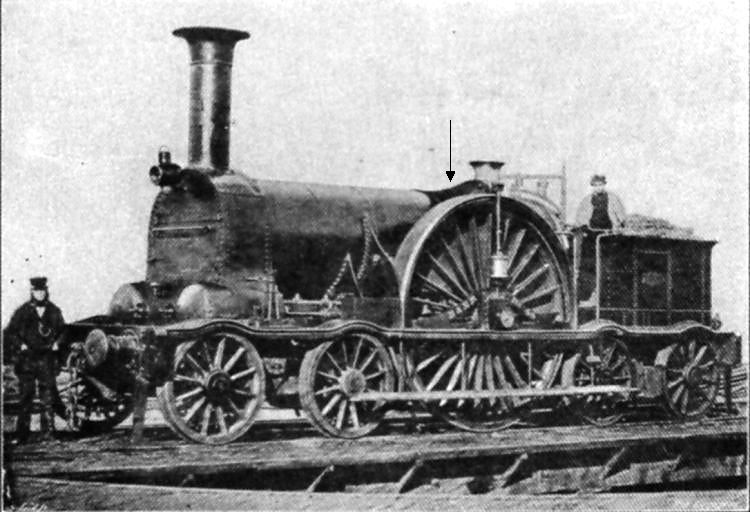

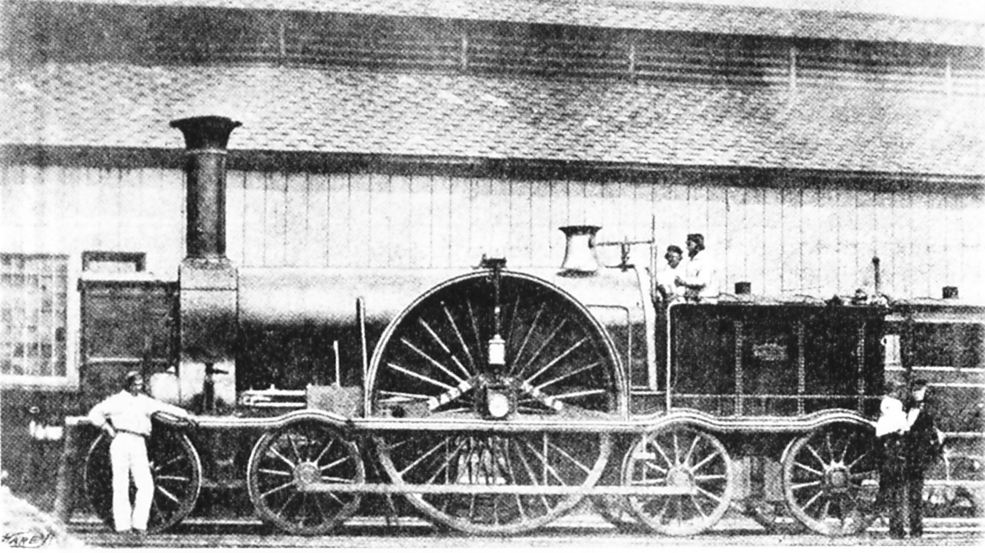

Above: The Pearson 9-Foot single of 1853, bearing a magnificent tuba-like chimney. Arrow shows boiler bracket.

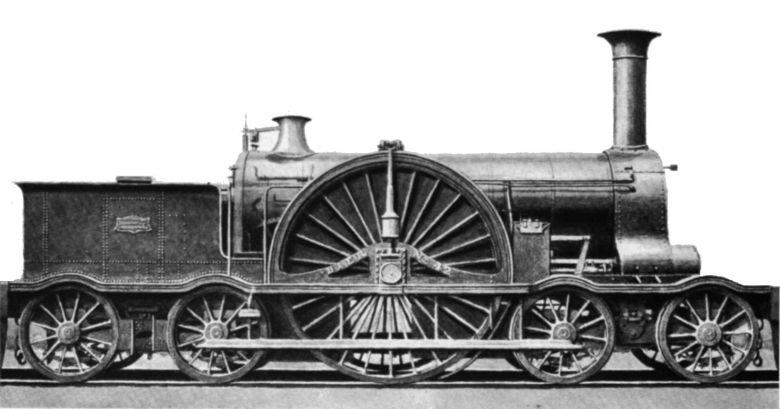

Several other features of this engine's design have attracted comment; for example the smokebox was unusually short, and the ends of the cylinders can be seen protruding ahead of it. The suspension for the enormous driver was a peculiar arrangement of four india-rubber discs, on each side of each wheel. The outside cylinder containing these discs can be seen just above the axle. The wheel load was then transferred via frighteningly thin vertical rods (in compression!) to the large bracket riveted to the top of the boiler; (arrowed) the boiler in turn passed the load to the inside frames. This seems a very doubtful arrangement, but we may never know if it gave trouble as records of this design's performance do not seem to exist.

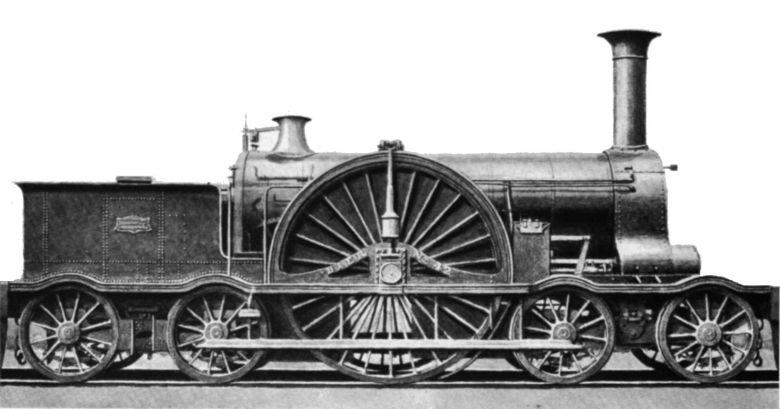

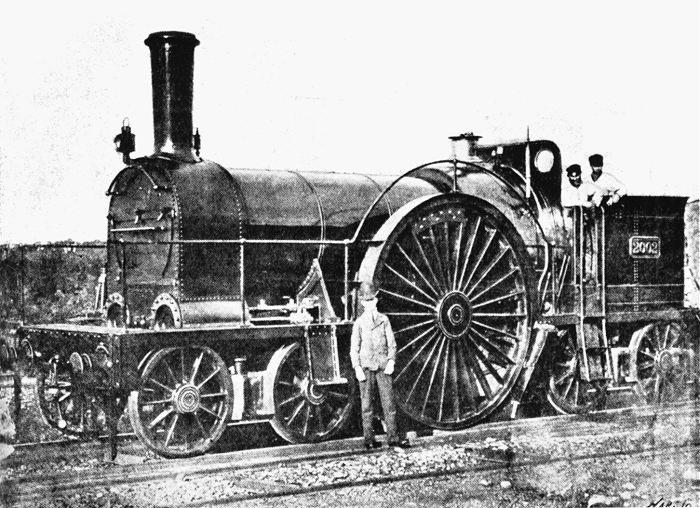

Above: The Pearson 9-Foot single portrayed in rather better photographic quality, but without the human figures that show just how big it was.

These locomotives had an average life of only sixteen years, which seems to show that they left a lot to be desired. Very possibly there was insufficent adhesion weight- after all, only one out of five axles was driving. According to one source, all eight were scrapped between 1868 and 1873. It appears however, according to Charles Rous-Marten, (writing in The Railway Magazine, August 1897) that in fact they were rebuilt when the Bristol & Exeter Railway was abosorbed by the Great Western in 1876, and then later rebuilt again as tender engines with the wheels reduced to 8-foot in diameter. They ran equally fast with the new wheels and continued to give excellent service until the broad-gauge was abolished in 1892.

Above: Side-elevation of the Pearson 9-Foot single: 1853

|

|

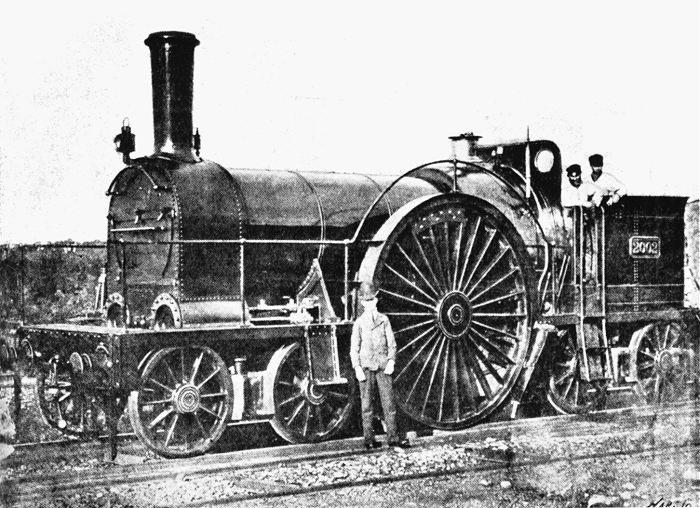

Above: Pearson 9-Foot single. The railwayman on the right seems to be carrying a small child.

|

|

| Left: Pearson 9-Foot single at Exeter after first rebuild: 1876

The precarious-looking suspension arrangements have been swept away, and the smoke-box extended forwards (presumably in an attempt to improve steaming) so it is about the same length as the cylinders. The tuba-chimney has gone, but a spectacle-plate has been added to give some protection to the crew.

The 9-foot wheels remain.

|

Sectional illustrations of these engines are to be found in The Engineer supplement for Dec 16, 1910. Run, don't walk, to the nearest library.