The era of silent films lasted from the late 1890s until the adoption of the "talkies" in the late 1920s. From the begining the lack of sound was recognised as a serious drawback, and many schemes were evolved for keeping phonograph records in sync with the pictures, usually with little success.

A common plan was to employ musicians who would (hopefully) play music that corresponded with the film action eg love scenes versus police chases. However this was often not considered good enough, and there grew up a whole profession of sound effect artists who attempted to reproduce thunder, horses's hooves, and soldiers marching, using simple mechanical devices that were often called 'traps'. A familiar example is using two coconut-shell halves to simulate a horse's hooves. Sounds effects were also used in making radio programs.

Theatre organs such as the Mighty Wurlitzer could simulate some orchestral sounds and of percussion such as bass drums and cymbals, and sound effects ranging from "train and boat whistles to car horns and bird whistles; ... some could even simulate pistol shots, ringing phones, the sound of surf, horses' hooves, smashing pottery, and thunder and rain" (Miller, Mary K. April 2002. "It's a Wurlitzer") However these enormous instruments were very expensive and wholly unsuitable for the average cinema.

|

| Left: The Excelsior Sound Effects Cabinet: 1913

The Excelsior Sound Effects Cabinet combined a large number of sound effects in a compact console. There are various handles, cranks, and levers to operate the effects. None of them seem to be labelled.

Unfortunately the Museum Staff have so far not been able to find a list of the built-in effects, which should be fascinating. Can anyone help?

Source: Motion Picture News, Vol 8, No 18, 1913

|

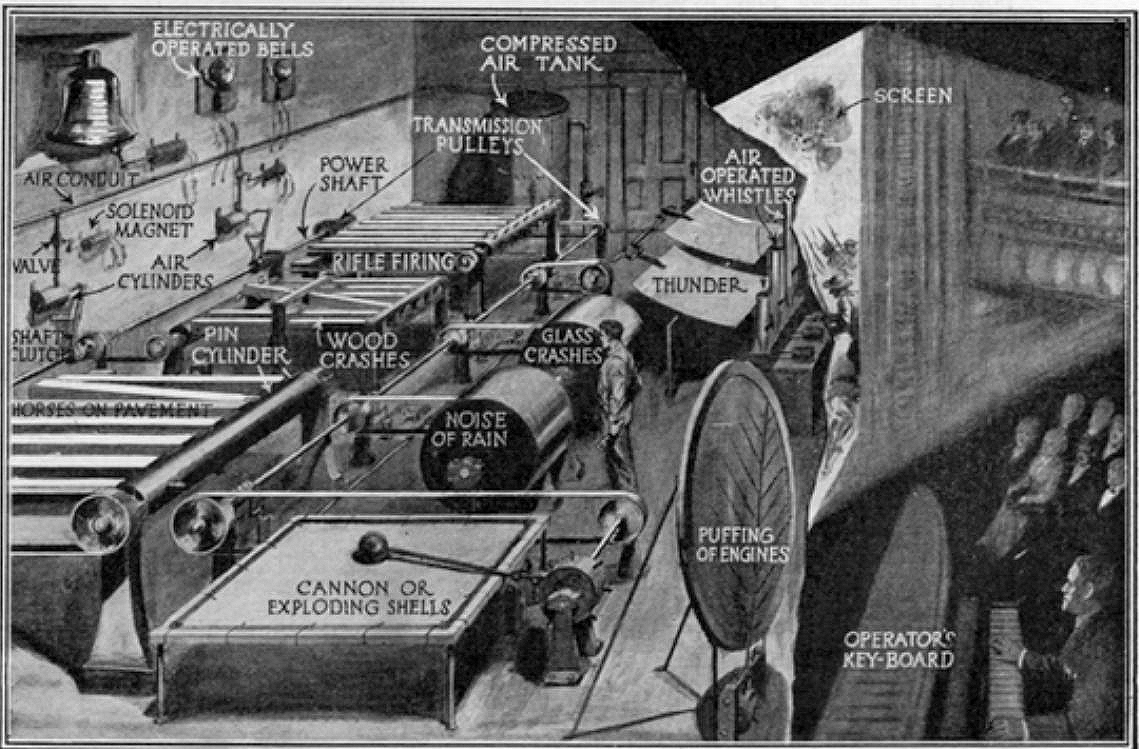

FRANK ILLO'S CINEMA EFFECTS MACHINE: 1918

|

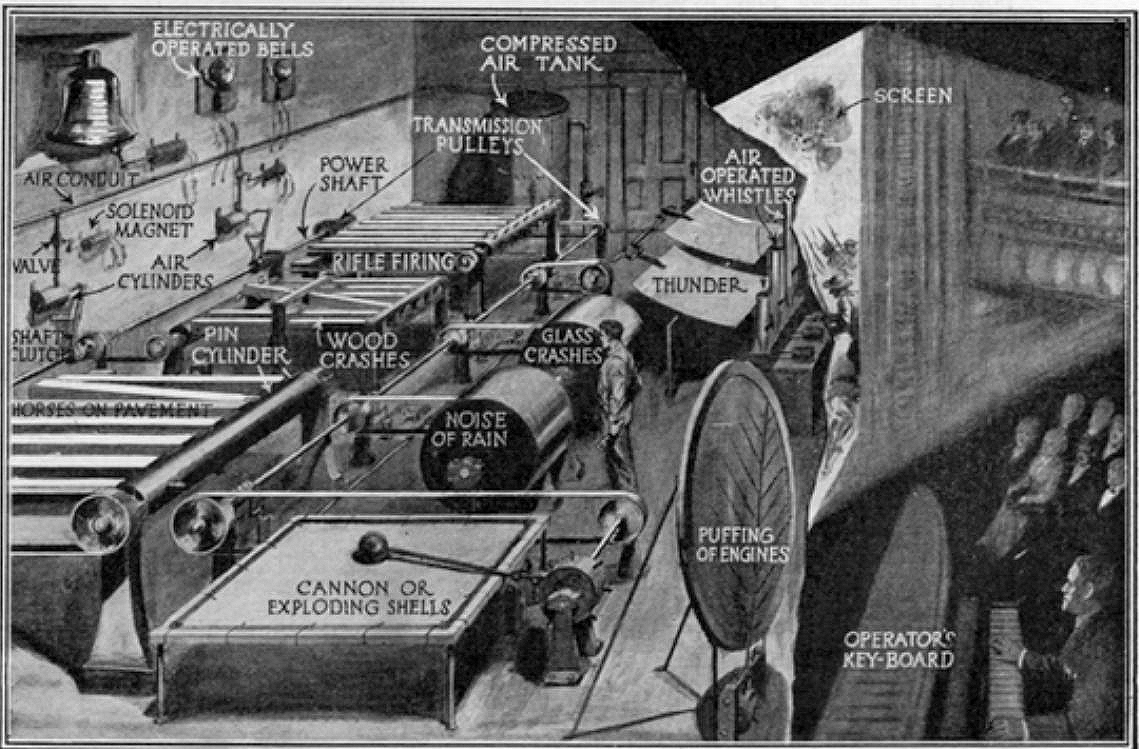

| Left: Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine: 1918

This superb illustration shows the concept of Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine. This is a drawing or painting. As far as is known at present no machine was ever built and installed. Note that a lot of space is required behind the screen, which would have been fine in converted theatres but impossible in purpose-built cinemas.

Source: Popular Science magazine, September 1919

|

|

| Left: Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine: 1918

This is the patent drawing of Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine that was used to create the illustration above. The drawing has been split into two halves to make the numbers legible.

Assembly C (the patent calls it an 'instrument') at top left operates when a solenoid (shown with curly wires) opens a air valve to operate a piston in a cylinder that engages a clutch on the line shaft 9. This, via belt and pulleys, causes a pin-studded drum 27 to rotate and the pins pull back and release spring-loaded slats that then hit a wooden beam to simulate the sound of rifle shots.

Assembly B at bottom left works in a similiar fashion to produce the noise of a wooden structure collapsing, eg a bridge.

Assembly E at bottom centre is a rotating drum filled with lead shot or steel balls to simulate the sound of rain.

Assembly F at the centre is a rotating drum filled with broken glass to simulate the sound of breaking windows.

Assembly G at top centre is pair of metal plates that are waggled by cranks to simulate thunder.

Assembly H at mid right simulates the sound of a puffing locomotive and consists of a thin metallic diaphragm or sheet 41 suspended between a frame 42. An arm 43 is

pivoted to a shaft and provided with a great number of light metal ribs or preferably wires 46 are arranged in a cluster and in brush form from the extremity of the arm for the purpose of lightly impinging the metallic diaphragm.

Source: US patent 1,278,152 of Sept 1918

|

|

| Left: Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine: 1918

This is the bottom half of the patent drawing of Frank Illo's Cinema Effects Machine.

Assembly A at bottom left simulates the sound of horses on pavement.

Assembly D at lower centre consists of a frame 29 upon which is which is tightly stretched a buckskin diaphragm 30. A big beater hits it to simulate distant cannon fire.

Assembly I at mid-right is an array of electric bells and buzzers that are energised directly. The big locomotive bell is rung by a solenoid.

Assembly J at lower right is an array of whistles and organ pipes controlled by solenoids that simulates train whistles and ship sirens.

Clearly the machine needs both a source of rotary power for the two line shafts, (which are not shown as connected) and also compressed air (at unknown pressure) to work. The patent says nothing about how they are to be provided.

Source: US patent 1,278,152 of Sept 1918

|

|

| Left: The Automatic Electric Orchestra Phonograph Array: 1918

One problem with adding sound to silent films was that even if you could maintain sync between the film and the phonograph, the volume of the latter was completely unable to fill a theatre. The Automatic Electric Orchestra Phonograph solved this by having no less than 48 phonographs working in parallel. Each had a horn and a tone-arm that reproduced sound from a separate track cut into a strip of film. The film was moved by an electric motor.

This at a stroke solved the volume problem, and would also have resulted in much better sound quality as each instrument would have its own channel and there would be no intermodulation distortion, which is what makes phonographs sound so awful. Forty-eight channels? Now that's what I call multi-channel reproduction.

The illustration shows two rows of horns so there must have been 24 in a row, stretching the width of the screen. This immediately suggests that stereo effects could have been created by suitable pre-processing of the tracks on the film.

There is not much more info here.

Source: Electrical Experimenter for February 1918, p660. The article gives very little technical detail, but we do learn that the film carrying the audio was less than 2 inches wide.

|

|

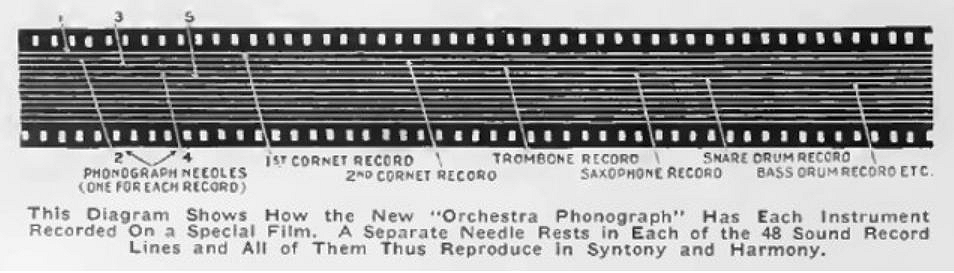

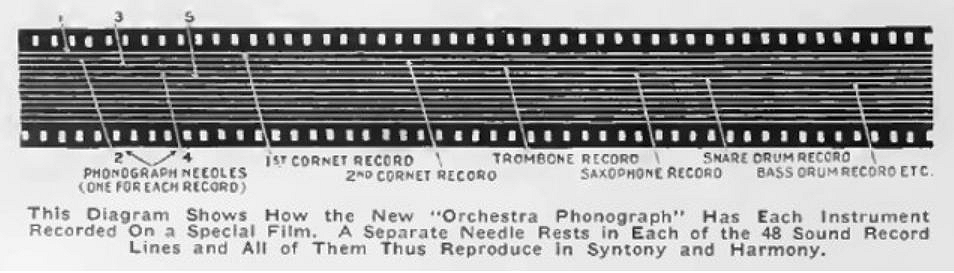

| Left: The Automatic Electric Orchestra Phonograph: 1918

This is an image of the film strip used by the Automatic Electric Orchestra system. There are only 12 tracks in this image, implying that there were four separate film strips running in (hopefully) perfect synchrony. This should have been relatively straightforward because of the sprocket holes in the film; synchronisation with the on-screen action would have been another matter altogether.

Source: Electrical Experimenter for February 1918, p661

|

Recording the films would have been a tricky business, because since the pickups were displaced laterally, two notes intended to play simultaneously would have been offset on the film.

The system was developed by the New York electrical engineer Mr H Hartman, who so far appears to be unknown to Google. The article in Electrical Experimenter says that patents have been taken out, but no patent has yet been found yet. Mr Hartman had Previous, having designed a speaking clock in 1917.

Nothing has so far been found to suggest this machine was ever built.

|

| Left: Sound Effects cabinet at radio station WMAQ in Chicago: 19??

This Sound Effects cabinet was used at radio station WMAQ in Chicago. Unfortunately the labels on the controls are not legible. Many of the controls are handles dangling on cords that were called 'cows tails'. Some the controls appear to be foot-pedals.

The man sitting is blowing a whistle

Why the man on the left is dressed up as a European policeman is unknown. He seems to checking if the vacuum cleaner is overheating.

Source: also unknown

|

|

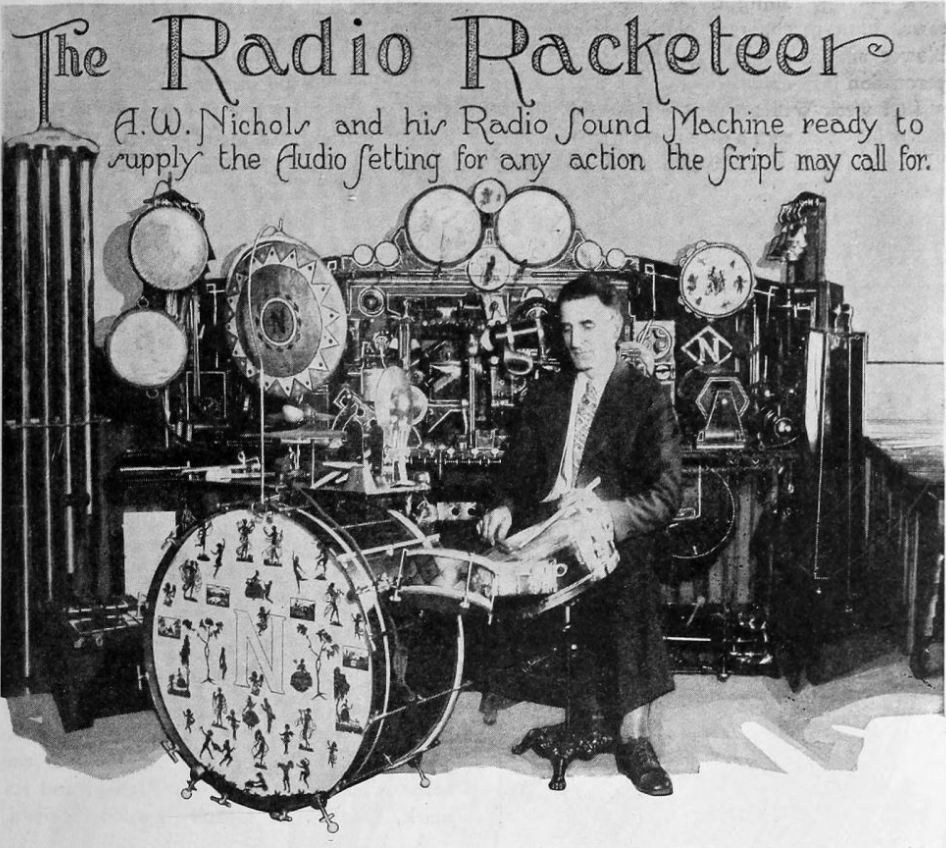

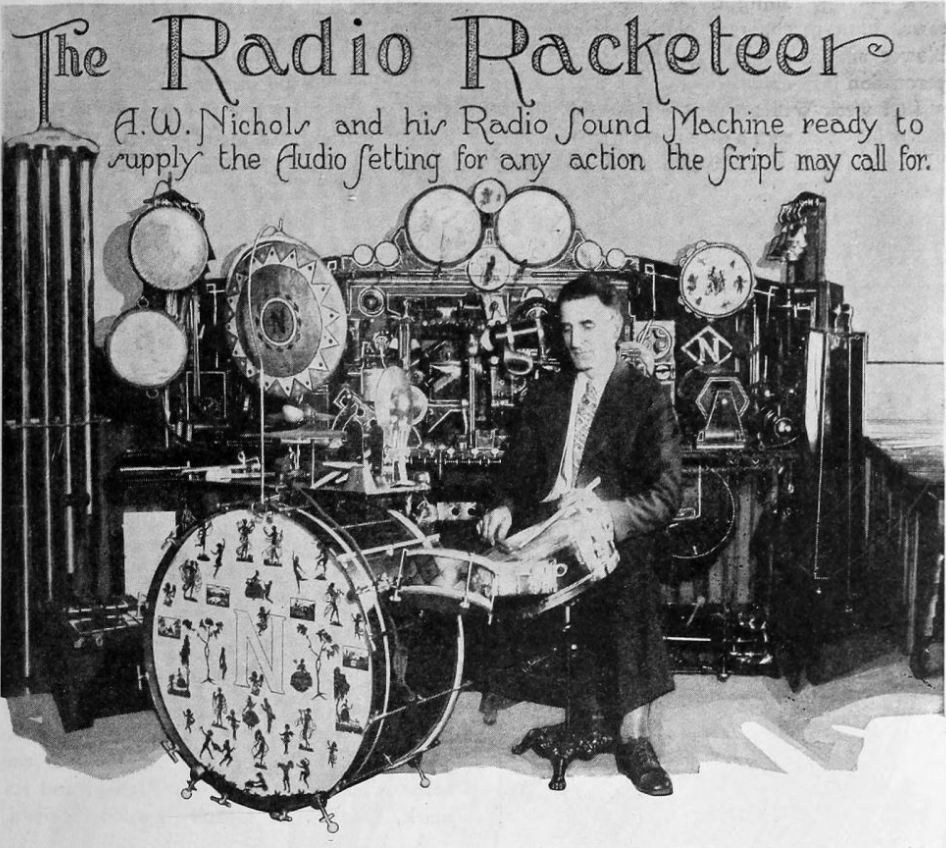

| Left: A promotional card for the Radio Sound Machine of A W Nichols: 1930

A promotional card for radio sound effects practitioner A W Nichols. He sits at a conventional drum kit while behind him is a vast cabinet apparently holding a large number of sound machines. He was married to another sound practitioner Ora Nichols.

According to the Wikipedia article on Ora Nichols, the cabinet was powered by nine (presumably electric) motors.

At the extreme left: four tubular bells.

|

According to What’s On the Air magazine, which describes the cabinet as a table:

"The table took him nearly a year of steady work, averaging from ten to fourteen hours per day, to build, but it seems equal to every call dramatists can make on it.

The more popular sound effects are keyboard controlled. One button releases the ocean surf; another, the thunderstorm; another, gales of variable intensity. Then there are buttons for train effects (steam and motorized); aviation fields, fire department, automobiles, motorcycles, city street, riveting-machines, trolley cars, machine guns, crashing glass, revolver or rifle fire, and a myriad others and combinations of all."

"One side wall is devoted to whistles of every description. The center back is capable of reproducing the sounds of barnyard or zoo, or of any individual denizens of either. The right side wall is for bells, buzzers, telephones, wireless instruments, machinery sounds of many types. Room has been provided also for Old Dobbin and the buggy, anvil, door slam, clock ticks, fireworks, baby cry, chain rattle, sleigh-bells, board squeak, sword duel, flies, bee buzz, cork pulling, falling trees, various types of saws, blow-torch, real cloth tearing, nose blower and a hundred and one varieties of percussion instruments."

|

Source: What’s On the Air magazine for April 1930. There is more info on A W Nichols here.

THE SOUND EFFECTS ARRAY OF ALBERT STINTON

|

| Left: The Sound Effects Array Of Albert Stinton: 193?

Here Mr Stinton has an effects cabinet and a table. The round thing in front of the table has a rotating arm with a wheel at each end and was probably used to simulate the sound of moving vehicles. Note 'Colombia' on the central microphone.

Mr Stinton is unknown to Google.

|

THE SOUND EFFECTS ARRAY OF RAY KELLY

|

| Left: The Sound Effects Array Of Ray Kelly (NBC): 19?

Some of the effects here are helpfully labelled.

There is an ominous-looking gas cylinder standing vertically in the centre of the picture; its purpose is unknown, The cylinder is colour coded to indicate its contents, but this is a black-and-white picture so we will probably never know what gas was in use, nor what it was for. Blowing up balloons and bursting them to simulate gunshots? This is pure speculation by me.

Note 'NBC' on the central microphone.

|

THE SOUND EFFECTS ARRAY OF MS MOODY

|

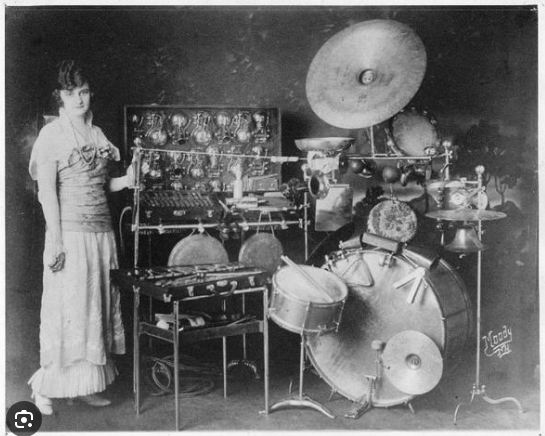

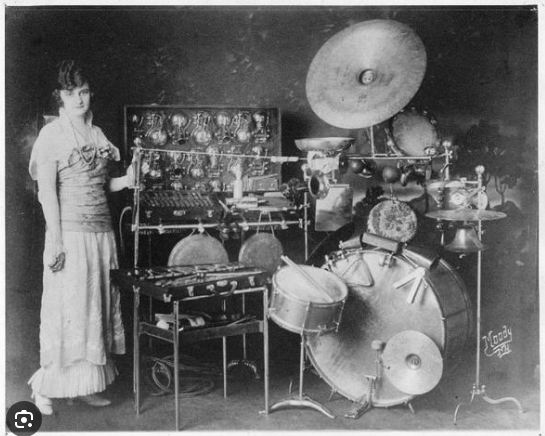

| Left: The Sound Effects Array Of Ms Moody: 19?

To my chagrin I have lost the information on this image. All I can tell you is that this array belonged to Ms Moody. She is unknown to Google.

I would be very grateful if anyone can supply any information.

|

THE PHOTOPLAYER

|

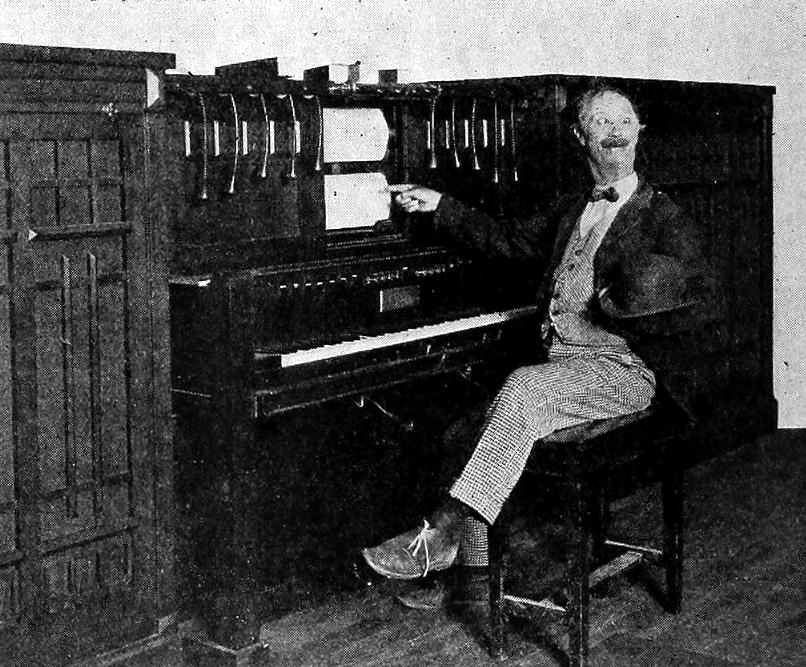

| Left: A Photoplayer with actor Ben Turpin: 192?

The Photoplayer was an an automatic instrument based on a piano and percussion, controlled by piano rolls; it could therefore be operated by relatively unskilled persons. It carried two roll-readers so that one could be prepared while another was playing, to avoid awkward silences. It also produced sound effects, some of which were housed in cabinets either side of the planola. Note the hanging 'cow-tails' (graduated in length) for operating the effects manually.

Seated at the Photoplayer is silent comedian Ben Turpin, famous for his cross-eyed appearance, helpfully pointing out one of the roll-readers.

Why was it called a Photoplayer? Not because it played back electro-optical images, as it was controlled by piano rolls. It was because it was intended to reproduce a genre called Photoplay Music, short bits of incidental music (often lasting only a minute) that could be compiled to make up an accompaniment to a silent film.

The Photoplayer has a Wikipedia page.

|

|

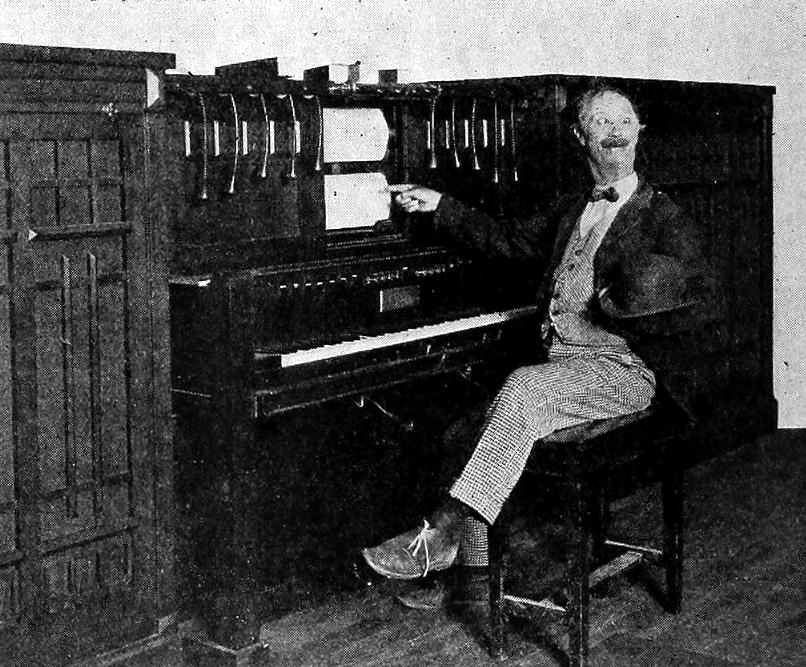

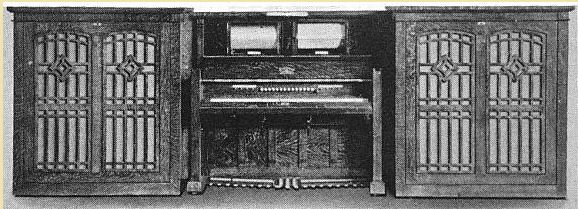

| Left: A Cremona M3 Fotoplayer : 19??

The Fotoplayer was one make of Photoplayer, produced by the American Photoplayer Company. I don't know why they felt it necessary to play about with the spelling.

Thousands of Photoplayers were built in the silent film era. They were generally installed in smaller cinemas, as without amplification they were not loud enough to work in larger theatres. Peak production was in the late 1910s, tailing off rapidly after 1925. They seem to have been rapidly scrapped when talking pictures arrived, probably because they had very little other use apart from accompanying film. Only a hundred or so exist today, and only about twelve are playable.

The American Fotoplayer has a Wikipedia page.

|

There is more Photoplayer info here, and also here.

There is a bulletin board dealing with Photoplayers here.